From Princes to Sages

John Haberin New York City

Companions in Solitude and Early Buddhist Art

In the year 405, a Chinese magistrate made a bold move—not to seize still greater power, but to step down. He chose, as the Met puts it, to "remove [himself] from the flow," apart from the courtroom, the court, and their worldly concerns.

Not that a modest life meant a life without pleasures. He tended chrysanthemums, overflowing even his artistry, and he had plenty of time for drink. Nor did life as a recluse mean a life alone. He may or may not have raised a toast when he drank, but others did, and Lu Han made nature the setting for an entire pavilion for an aging drunk in 1659.  Among other famous recluses were the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. They and the magistrate were just two foundational myths in "Companions in Solitude."

Among other famous recluses were the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. They and the magistrate were just two foundational myths in "Companions in Solitude."

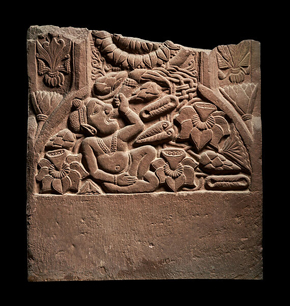

As a title, "Tree and Serpent" is less an umbrella than a teaser for six centuries of early Buddhist art. And the Met opens a second show of Asian art with a limestone slab carved with just that—a tree, its branches like a sea of umbrellas in the rain, and, below, a coiled snake. As part of a stupa, or burial mound, they would have brought enlightenment and protection to pilgrims, just as they did to Buddha himself. He might have sought a tree for protection from the elements, much as one seeks a tree or an actual umbrella today, but he found something finer—the inspiration to change his life. The serpent in turn then promised its protection. But then Buddhism, like its predecessors, teems with nature gods and goddesses, at once fiercely demanding and bringers of life.

What you will not see is Buddha himself. That makes sense if you remember that the stupa held and protected his remains. The very first one did upon his death, although the story changed soon enough so that the kings of the earth each took some of his bones. In due time, pretty much any local culture could have its stupa as a destination and common ground. The Met, in fact, constructs a replica for anyone to enter, holding precious stones and other relics. A burial mound may call to mind a makeshift pile of dirt, but a proper one would have had a dome covering two tiers of a circular walkway, its guard rails and pillars as intricately carved as the serpent and the tree.

Absence makes sense, too, if you bear in mind what had changed. The young Siddhartha very much needed enlightenment if not protection, as a profligate and a prince, and nature delivered. It taught him to scorn the body, as the awakened one, or Buddha. Enlightenment may have come more than two centuries before the show's starting point in 200 B.C.E. or far earlier still. If the stories keep changing, with a huge gap after his death, such is myth. If tales of a prince of power renouncing everything but contemplation has its echoes in Chinese art at the Met a year or so before, such is myth as well.

A guide to the reclusive

You may go to museums expecting companionship in solitude—and I do not mean the ugly crowds at blockbusters or barring the way to Vincent van Gogh. You can always find privacy amid friends and strangers alike in the Met's Astor Court, which recreates a Chinese scholar's garden. Still, the very idea of a public space for contemplation underlies centuries of Asian art, give or take an occasional demon or a dragon. Contemporary Asian art has its urgency and its chaos, and global diversity has its terrors, as in African art, but this wing stands apart. And the Met has rehung much of it for what a subtitle calls "Reclusion and Communion in Chinese Art." It avoids crowding the art at that, with works in two installments.

It could serve as a guide to an entire tradition. Chinese art has its evolution, often toward harder edges and a clearer sense of distance, although I am in way too over my head to offer much of a guide. Still, artists kept looking back to earlier myths and earlier styles, for a deceptive unity. One can count on blank areas of paper, for gaps between near and far, as with Shitao in 1702, and sudden shifts in point of view from the sky to the ground. You may think of this painting as akin to calligraphy, but that hardly explains the fine detail of reeds and architecture for Liu Songnian in the twelfth century or the brushy drama of mountains and clouds for Fu Baoshi in just the last hundred years. Mere shadows in the rocks may be the most calligraphic of all.

They are united, too, by being in touch with others through nothing more than subordination to nature. Finding the recluse can resemble a game of Where's Waldo. Still, the human presences keep mounting the longer one looks, along with hints of human artistry and intervention. For starters, if one cannot renounce the city and community, one can always create a garden. One can, that is, with sufficient means and a fashion sense, and the Met speaks explicitly of the "elegant garden." Wu Li shows a proper gentleman enjoying his garden, as Whiling Away the Summer from 1679.

Even in nature, subjects need not give up their occupations, no more than their pleasures. The museum speaks of the recluse as distinct from a traveler or a laborer. Yet recluses here can be fishermen at work or, with Zhang Lu, with family. They count as scholars because their very existence depends on nature. Sure enough, the Met describes a fishing village for Li Jie around 1170 as "one of the earliest depictions of a scholar's country retreat." Most of the show, though, dates from four centuries, starting with Wen Zhengming under the Ming dynasty, shortly before 1515. He, too, painted a summer retreat, and one can always count on an end to summer vacation.

Human preoccupations appear, too, in images of women. They pose much like men, but often together, and more than one appears on a fan, a female accessory. More generally, human arts appear in the mix of painting and such crafts as ceramics and actual Chinese calligraphy. One need not distinguish art and design—not when ceramics bear some of the most vivid landscapes in white and blue. They can also be censers, for a religious ceremony, or a place to rest brushes for paint. Calligraphy can function as a colophon, the page identifying an artist's book, or as poetry or letters for an artist to illustrate.

Not coincidentally, recluses in art may use the time to write poems or letters. They do so alone, but to share their discoveries and to stay in touch. Nature, in turn, can be the subject for contemplation or its enabler. In two of the most common motifs, a scholar marvels at a waterfall or finds shelter beneath a tree. Gentle or turbulent, nature's motions will continue long after the painting is gone. But then, art's stillness will persist long after the exhibition has ended, too.

The tree of life

I knew little enough coming to the origins of Buddhist art, but I had to forget everything I knew. Think of fat enthroned Buddhas and bodhisattvas, his attendants in enlightenment, like a TV Buddha for Nam June Paik? Cast or carved, Buddhas turn up only in the Met's last room. Think of Asian art as a world apart? Routes opened between East and West earlier than you ever knew—for trade and, in centuries to come, European empires. A room for the interchange has a miniature Poseidon, the Greek sea god but here from Indian art, not wielding his trident but leaning forward with one armed raised and one foot on a stoop, in no need of asserting more. Two carvings of a robed Buddha in the last room have repeated folds like those in ancient Greek and Roman reliefs of women.

Then, too, you can forget what you knew about western art. That may go without saying in approaching the East, or does it? Surely art after classicism became sterner, more frontal, and inhuman, like those seated Buddhas but flatter and bearing no weight at all. Then came the Renaissance, the story goes, with humanity in every way in the round. The East could only choose one or the other, right? While Siddhartha lived in Nepal, the Met sticks to the south of India, with support from India's minister of culture. That could only bring contemporaryIndian art further from the fluid line and feeling of not just European realism, but Chinese art as well.

Then, too, you can forget what you knew about western art. That may go without saying in approaching the East, or does it? Surely art after classicism became sterner, more frontal, and inhuman, like those seated Buddhas but flatter and bearing no weight at all. Then came the Renaissance, the story goes, with humanity in every way in the round. The East could only choose one or the other, right? While Siddhartha lived in Nepal, the Met sticks to the south of India, with support from India's minister of culture. That could only bring contemporaryIndian art further from the fluid line and feeling of not just European realism, but Chinese art as well.

So you may suppose, but Buddhist art never had to make a choice. It had something very different all along—extravagant and in low relief. That matched its view of nature as superhuman but a giver of life. That also matched its symbolism. Think of the seeming umbrellas and the serpent. Its coil becomes a wheel, shorthand for Buddha's teachings, a perfect circle driving ahead. Its dangers and protections extend to a winged lion on a pedestal high above one's head.

The curator, John Guy, opens with stupa and their carvings. Many center on figures, twisting and gesturing, surrounded by plants. Their mask-like features only add to their vivid expressions of pleasure or disgust with, say, you. Buddhism may preach asceticism, but panels teem with nature, and their figures feast on it, swallowing it whole—unless, of course, it is emerging from their mouth. Relish the contradictions, and relish, too, the presiding deities in the next room. Relish as well the signs of Buddha's absence, including a footprint, a flaming pillar, a riderless horse, and the relics.

Over the centuries, as happens, the reformers become the establishment and the artists servants to power. The wheel turns beneath charioteers, and the horse without a rider gives way to royalty atop elephants. More than one sculpture is gilded. Carvings become still more varied and intricate, akin to crowd scenes. They adopt compositions in rows, to bring order to this newly embraced chaos. Even before Buddha's first appearance, his teachings acquire narratives beneath the tree of life.

Like those robed Buddhas, figures also have an ambiguous sexuality. They do come gendered, like nature gods as Yakshas and Yakshis. The first demand offerings of wine and blood, while the second return the offers many times over. Yet they, too, are rich in contradictions. I cannot claim to have mastered their history from a single show. I can, though, see how much I have missed.

"Companions in Solitude" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in two parts, through January 9 and August 14, 2022, early Buddhist art in India through November 13, 2023.