Meet Me at the Met

John Haberin New York City

Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas

Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Fauvism

Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas met in the Louvre, and why not? How many artists today first met at a gallery—or at the Met? But of course there was more to it. There always is.

"Manet / Degas" at the Met describes an extended meeting and a falling out. It has more than enough room for both figures—their habits, their families, and their friendships as well. And then you, too, can start asking questions.  Just how close were they over more than thirty years, and what took them their marvelously separate ways? What were they doing in the Louvre to start with? Degas still had trouble putting his finger on it in looking back.

Just how close were they over more than thirty years, and what took them their marvelously separate ways? What were they doing in the Louvre to start with? Degas still had trouble putting his finger on it in looking back.

The, Met, twice over, quotes him from after Manet's death (from syphilis at just fifty-one): he was greater than we thought. That may sound like a left-hand compliment, but it came with real regrets. They had pursued together the working class, the still-new bourgeois interests that it served, the delights that it found for both, and the cruelty that kept breaking out along the way. The show's greatest rarity, Olympia, now on its first visit to the United States, depicts a courtesan with the implied customer as you. How, then, did each artist's fascination with past art get along with the urge to make it new?

"Manet / Degas," the year's blockbuster, shows two great artists learning from and struggling against each other. Even more, it shows their course from the Louvre to modern life. What would it take to go the rest of the way, from Post-Impressionism to modern art? Could it have taken two more artists working side by side? "Vertigo of Color," in the museum's Lehman wing, follows Henri Matisse and André Derain to a fishing village in France for a single summer. It marked a powerful convergence, celebrated or derided as Fauvism, but just as interesting is what it leaves out.

The modern museum and modern life

Make it new. The line dates to Ezra Pound many years later—when Edgar Degas, too, was dead, Dada was long past, and Cubism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and more had gone their separate ways. And it still rings out in the sheer imperative of modern art. So why then does Edouard Manet draw on Titian and Francisco de Goya for the nude in Olympia. Why does he quote an engraving after Raphael by a lesser Renaissance Italian, Marcantonio Raimondi, for Déjeuner sur l'Herbe (or "Luncheon on the Grass"), also in 1863—and why do both paintings still feel new? Surely it has to do with fine art and the edge of modern life.

Both artists knew the lure of both. They ranged seemingly everywhere, starting in the Louvre. Both made copies after Eugène Delacroix, of the Middle Ages in French Romantic color. Both looked to scenes from the New Testament in Italy, by Titan and Andrea Mantegna, and the modeling of Renaissance drapery. Both sketched self-portraits after Filippino Lippi, the student of Botticelli, one looking younger than the next. And they had not yet met once.

That changed in 1861 or 1862, when they bonded over a portrait of the Infanta, the royal daughter, by Diego Velázquez. Both young men had a fondness for Velázquez and Spanish painting. They admired Goya, too, for a frank look at the disasters of war. It must have seemed the only course for an artist determined to rank up there with tradition but stifled by formal academies and academic nudes. No wonder they were ready to explore Paris. They had each other now, and they had taught themselves fine art.

Set Raphael's nude in a park in France, on an outing with bourgeois young men, and you have a scandal. Make that a triple scandal if the trees are as raw as sunlight and their depths as unexplained as death. Set Titian's nude in a brothel or not much better, with her black servant gaping out at you, and artists will be revisiting it to this day (at Columbia's Wallach Gallery for "The Black Model" in 2018). The bouquet you brought seems as flat as a postcard but costly as can be, the linens so textured, the brushwork feathery but bold, that you touch at your own risk.("Manet / Degas" has a large oil study for one painting and the original of the other.) It takes Manet to see women, without condescension or approval, as black and white.

Did Manet and Degas get along? No one knows quite how much and how long. The father of Degas hosted concerts, and Manet attended. (The Met judges him ignorant of music, from the fingering of his Spanish Guitarist, but I am not so sure.) Degas, in turn attended events hosted by Manet's closest follower, Berthe Morisot, and so did Degas. She married Manet's brother as well.

She also sat for Manet, for whom a stylish black dress, loose black hair, and every mark of self-awareness and intelligence were tailor-made. Their circles ran, too, to art dealers and to writers like Stéphane Mallarmé and Emile Zola. For Manet and Degas, writers and writers were essentially collectors. Zola's seated profile for Degas, his study's careful arrangement, and the works on the wall anticipate collage. Zola's novels also take a girl from poverty to a brothel. Manet painted her standing, as vivid as a portrait.

Private gatherings and public fictions

Not that they settled for private gatherings and public fictions. They went together to the track, the dance, the music hall, the cafés, and the clothiers. Yet their temperaments diverged along the way. Manet shows riders racing headlong, Degas a fallen jockey and the long, slow preparations for a race. It anticipates his focus on dancers testing themselves for an unseen instructor. It parallels, too, Manet's catching you in the action, from sex to the park. It took a very different kind of detachment from Claude Monet by the Seine or Paul Cézanne facing his wife.

They differed, too, in their space between subjects. Manet finds café society in a woman alone with a plum brandy. Degas finds it in a couple who cannot so much as look at either other, while the frame cuts off whatever the man sees. Both nurse a liquor that everyone knew was poison. Of the two artists, Degas sees human psychology in more explicit terms and measures every drop of it in physical distance. You can construct a history of his Bellelli family, a group portrait in black, in just who turns to, who commands to, and who clings to whom. Every inch counts.

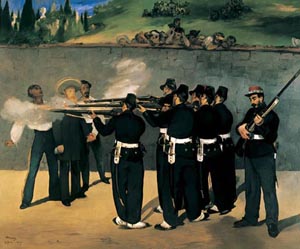

They differed explicitly in their politics. Both took an interest in the American Civil War—Manet in a Union victory, Degas on the trading floor of the cotton exchange in the South. He had family money there. Manet in turn knew the cost of tyranny but could not take comfort in victory. At the execution of Maximilian, emperor of Mexico, he shows a lone soldier at rear reloading, indifferent or in charge. The rest find their own anonymity in a puff of smoke and the discharge of a barrel.

Yet they differed in their radicalism within art institutions as well. It neither began nor ended in the Louvre. They were also conflicted. Degas helped to found the first Impressionist exhibition while hating the label Impressionist. Manet declined to join, with mixed feelings about Impressionism as well. Yet his name will always be tied up in the display of Déjeuner sur l'Herbe at the Salon des Refusés. He had made the course of art history new.

Yet they differed in their radicalism within art institutions as well. It neither began nor ended in the Louvre. They were also conflicted. Degas helped to found the first Impressionist exhibition while hating the label Impressionist. Manet declined to join, with mixed feelings about Impressionism as well. Yet his name will always be tied up in the display of Déjeuner sur l'Herbe at the Salon des Refusés. He had made the course of art history new.

The curators, Stephan Wolohojian and Ashley Dunn with Laurence des Cars (of the Louvre) and Isolde Pludermacher and Stéphane Guégan (of the Musée d'Orsay), show it all. Throw in Manet's Bar at the Folies-Bergère and a few more ballet dancers from Degas, and they would have had a dual retrospective as well. An artist or two really should meet you here. The show opens with paired self-portraits—Degas in sober black handled loosely, Manet unkempt in everything but paint. It includes ten prints and drawings of Manet by Degas from 1868 alone, plus a portrait of Manet and his wife that Manet hated for reasons unknown. Degas sliced it up and carried it off, but he could not have been pleased.

Textbooks may label Manet as Pre-Impressionist and Degas as Post-Impressionist, although the first was just two years older. It makes one artist a mere precursor and the other a footnote. Think of them instead as parallel roads to Modernism and modernity. Degas paints casual poses with a dour precision. Manet paints modern life in all its intricacy, as if he had laid it on that minute. The world for Degas is in progress, and you may not know where it will end up. The world for Manet is a drama, only not the one you wanted to see.

Beasts of burden

Just who were the Fauvists, or wild beasts? That fishing village, Collioure in 1905, looks remarkably serene. Sailboats lie still at their berths, their masts dipping like bridges across white, untroubled waters. Fishermen go quietly about their work, leaving deep blue traces on the shore. One can see why Henri Matisse called his most ambitious painting back then Luxe, Calme et Volupté (after Charles Baudelaire), with an equal emphasis on all three terms. His wife, Amélie, sits in a blue and white kimono beside the water, as if the drama of life had come to a perfect rest.

Or were the beasts the artists themselves, and was the wildness their art or the light? "The nights are radiant," Derain wrote, "the days potent, ferocious, and victorious. The light bears down on all sides with its immense shout of victory." The show's title puts Matisse first, because he will always come first, but the show itself opens with facing walls for André Derain. Daubs of red, yellow, and orange daylight cover the ground and a wild green enters the sky, like Pointillism for an artist too amazed to connect the dots. Yet he seeks stability as well, in the horizontals of the horizon, the shoreline, and the meeting between trees and earth. He finds it, too, in the detachment of a high point of view.

Yet things quickly intensify, as each artist paints the other. The shadow beneath Derain's chin divides his face between flesh and pale green, while the shadow beneath the other man's eye could have scarred him for life. Matisse himself is consistently the wilder beast, with color for its own sake in a deeper space with a logic all its own. Their titles alone draw a contrast—between Derain's care for the everyday labor of sailing and fishing, and Matisse's for landscape, mountains, and the joy of life. He has an instinct for generalization from this very moment. It may come as a surprise, in the show's third section, to discover that he painted Amélie outdoors on the spot, but he did.

The show wraps up with an extended postscript, for still life and portraits. A young sailor by Matisse could not conceivably get back to work without tempting those around him with his colors and curves. The section also takes the artists, if only briefly, into 1906. Derain brought what he had discovered to the sobriety of London at dusk. Both exhibited in the fall of 1905 in Paris. The Salon d'Automne set that year aside for Fauvism.

Yet that, too, leaves something out: the Salon counted Maurice de Vlaminck and others as Fauvists, too, in what had become not a summer's impulse but a movement. It leaves out as well Matisse's major works, such as Luxe, Calme et Volupté and the still greater color clashes of Woman in a Hat. Both exhibited at the Salon, but one would never know it here. The Joy of Life was soon to follow, as was the most startling of all, the portrait called (with good reason) Green Stripe. So was his ultimate breakthrough, starting in 1909 with Red Studio, and so was a very different meeting of the minds, rivalry with Picasso.

The curators, Dita Amory with Ann Dumas of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, leave all that out for a reason: they seek a point of origin in a pairing and a place. Matisse, they note, had been to Collioure before and would come again. Derain may have loved the night, but he never returned. Origins, though, have a way of receding into myth. This is beautiful art, but it stops short of the origins of Fauvism—or of modern art.

"Manet / Degas" ran The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 7, 2024, "Vertigo of Color: Henri Matisse, André Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism" through January 21.