Inside and Out

John Haberin New York City

Paul Paiement, Hilary Pecis, and "Shifting Landscapes"

Paul Paiement paints in the open air in the great American west, Hilary Pecis in the front yards and floral shops of Southern California. Paiement returns to a studied realism for an age that has seen it all come apart. Pecis may remind you more of pattern painting and the comforts of home. Which is closest to the promise of landscape painting and a bicoastal art world? Their story continues at the Whitney Museum.

I could not make it to the Whitney at dawn, and I could not have entered if I had. Still, on a screen by the window, sunlight crossed the horizon and reflected on the water. What could be more impressive than sunrise at noon—and more representative of landscape art? I should have read the title or, at the very least, noticed that I was facing west toward the Hudson. This is Artie Verkant's Exposure Adjustment on a Sunset, and the sun's hazy yellow sphere and broad band of white are equally an illusion. Give him a little time, and they will dissolve in pixels anyway.

The museum is out to alter the very idea of landscape in art, just as Verkant has taken it from painting to video. It sees contemporary art from its collection as "Shifting Landscapes." Its seventy-five artists also dissolve the distinction between human and animal, artifice and nature. It is oddly insular all the same. Maria Berrio could be speaking for them all when she calls a painting Universe of One. Still, if it seems at once arbitrary and downright incoherent, there will always be another dawn.

Just plein realism

Paul Paiement is a plein air painter, and you know what that means. Such an artist works on the spot, for the freshness of the afternoon, the freshest of impressions, and, tradition has it, the freest of brushwork. He is also a photorealist, for crisp, glistening, painstaking surfaces that record every detail and thrust it in your face. And then he is a trompe l'oeil painter, who can fool you into taking collage for paint and painting for the thing itself. If that seems a lot to handle, he keeps finding new ways to say "you are there"—and dares you to tell one from another. The labels can come later, if they apply at all.

Of course, those things cannot all be true at once, not for the most marvelous of painters. Paiement is not taking advantage of a glorious afternoon to take you up the Seine with Claude Monet and a boatload of the French middle class. Nor does he leave anything about the handling of his brush to chance. But Paiement does work outdoors, in the sun-baked American west. Impressionism led directly to the uncanny precision of Georges Seurat and Pointillism, but not even he would go there. If that sounds a bit forbidding for all its familiar glory, Paiement is all about bringing you close and standing apart.

He could be measuring out the distance. Where photorealism tends to mean portraits, including nude portraits, he has no obvious signs of life—not so much as the shadow of the artist or the feet of his easel. And where trompe l'oeil means still life, this is still landscape, and titles specify the location. It looks like collage all the same. Paiement paints on wood panels, leaving much of the grain exposed. He layers plywood strips and Plexiglas patches on top.

At any rate, I think so, because he can indeed fool the eye. One might mistake the painted areas for prints, torn freely and mounted on wood. Their edges look that dark and real. Even now I probably underestimate just how much is a single field of paint. Nor can I say for sure when clear Plexiglas allows a cloudy look at the surface and when Paiement continues to paint over the Plexiglas. Nature and handiwork come together.

Ultimately, he is painting, building an image of intense sunlight and measured shadows. Distant hills fade into the haze of saturated color, leaving that much more to move forward into the picture plane. The cloudiness of Plexiglas could be part of that haze. The wood grain in unpainted areas can seem part of the scene itself—or the same scene in a different season or under a different light. It is palpable but visual. It just may not be what you expect.

Paiement has worked closer to home, but always in sunlight. Past work in his "Nexus" series has included offices and industry in its imagery and architecture. Nature's pillars in his new work look almost manmade as well. Still, that kind of architecture is notoriously distancing. It is hard to imagine living in his work or escaping it. Painting has its illusions, its categories, and its myths.

Welcome to the neighborhood

Hilary Pecis opens her home and studio to visitors. She takes one into the lives of her neighbors as well without so much as a person in sight—and what lives they are, and what a life. Once you have been inside, you may never want to leave. You never could take it all in, not when her compositions run every which way and there is so much to see. It gives new meaning to "pattern and decoration" in painting, without an unbroken pattern and with too many specifics in time and place to write it off as decoration. Now if only you could be sure that you would not stand out like a sore thumb.

Pecis deals not just in sunlight, but in sensation. She brings you close to share the intimacy and outside to take in the view. Cats glare back, as cats do, but so near that they could almost be in your lap—or you in theirs if only they had one. Books fill shelf after shelf, and you may want to step past the flowers to inventory every title. Besides, books, too, can be an arrangement of shapes and colors. So can coffee cups, tablecloths, comfortable chair cushions, and the furniture to hold it all.

Pecis deals not just in sunlight, but in sensation. She brings you close to share the intimacy and outside to take in the view. Cats glare back, as cats do, but so near that they could almost be in your lap—or you in theirs if only they had one. Books fill shelf after shelf, and you may want to step past the flowers to inventory every title. Besides, books, too, can be an arrangement of shapes and colors. So can coffee cups, tablecloths, comfortable chair cushions, and the furniture to hold it all.

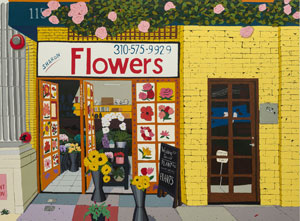

The bursts of sensation keep coming on a front lawn where trees and flowers compete with the architecture, white stones on red soil, and each other. Here, it would seem, people celebrate Christmas year round, to judge by a plastic Madonna and shepherds. But no, this is LA or an ideal version of it, where welcoming warmth and sunlight last through December. Still, a New Yorker would recognize the signs of home. The shepherds could pass for family by the porch waiting to see you, like Brooklynites on a stoop. Just one painting leaves home entirely, but there, too, for a single destination—and the shop sells flowers.

"Pattern and Decoration" arose in the 1970s as one more nail in Minimalism's coffin. Artists like Valerie Jaudon and Miriam Schapiro combined feminism and excess. It also proclaimed painting's special nowhere, where patterns matter more than what they cover. Pecis, in contrast, stuck to Southern California, but also to a sense of place. It seems only right that the flower shop gives its phone number on the awning. You could look up the area code online for a map of LA. You could look to the books, with an enviable choice of artists and philosophers, for a reminder of who you are.

Of course, they also define a class—a class of readers, but also of buyers. If the coffee cups have a further clash of geometry and color, you can assume that smart shoppers brought them home. These shoppers keep up with contemporary design and have the money to do so. But you could see that from the homes themselves, from the breadth of a porch and gabled roof to an alluring stairwell broken by shadows. I could easily feel guilty about belonging there. I may not live like this, but I do love the right artists and have read the right books.

Pecis can seem a lightweight—and ready confirmation of one's suspicions about money in art. The show opened the week of New York art fairs, with their display of wealth. Still, she is not taking the easy way out. Maybe the movement artists better known in New York would look less comforting if they shared her sense of place. Her very wildness disrupts a skeptical narrative as well. The flower shop has its own profusion of signs and samples.

A universe of one

You have seen this often enough before. A museum rolls out a genre from art's history and modernizes it in the interest of contemporary art and diversity. It could be self-portraiture, the female body, art's materials, or blackness. It risks becoming not so much a theme, since a show's rooms will have their own themes, as a tic. At the Whitney, Jennie Goldstein, Marcela Guerrero, and Roxanne Smith as curators take that model from the body into landscape painting. If neither landscape nor painting is all that evident, you will not be surprised.

That may be the Hudson out the west window, but this is not the Hudson River School. The very first room takes things off the canvas once and for all. Its theme of "Borderlands" makes sense when elections turn on immigration, but is art still crossing borders? Leslie Martinez applies pumice, paint chips, and rags, and you will just have to take her word for it that they reflect the accumulation of objects and cultures in a human life. Huge mossy creatures lie on a bed of turf for Amalia Mesa-Bains, while flames spread at night on a grid of ceramic chips by Teresita Fernández. She didn't start the fire.

The flames may refer as much to climate change as to borderlands, and the next section speaks to the altered landscape. Robert Adams photographs industrial sites in Colorado. Dance for Nicole Soto Rodríguez alludes to sites and customs in Puerto Rico, but as performed on video and on a luxuriant staircase at home. What, then, could show the land's transformation better than New York? Cityscapes here just may not have much to do with the urban landscape. They make room for Keith Haring, of all people, and (New York New Wave) Jean-Michel Basquiat.

See a pattern here? On the one hand, seemingly anything fits. On the other hand, pretty much anything that you might expect does not. That includes the entirety of history. This is not about mixing old work and new for fresh perspectives on both. Painters and photographers from the Ashcan School and the Harlem Renaissance to William Klein and Ming Smith have immersed themselves in the city, but not here. Just a floor below, a show for Alvin Ailey has ample space for the African American South. All "Shifting Landscapes" can show is a lone Gees Bend quilt and some cluttered assemblage.

The recent past does enter a room for earthworks—and just as quickly withdraws. Robert Smithson and Walter de Maria are nowhere to be seen, but Nancy Holt is, with the field locator that showed her the way. So is Agnes Denes, with photos of her wheat field in Battery Park City, seen from an angle that leaves their setting and subject a mystery. Maya Lin has her Ghost Forest of cedar stumps, but one would never know her concern for climate change. One would never know, too, how much she has reshaped urban spaces, from the Vietnam Memorial in Washington to museum architecture in New York. While hardly earth art, Gordon Matta-Clark does get to climb a tree and to call it a dance.

A final section, the curators argue, makes explicit the humanity of nature. If this, though, is "Another World," can it show humanity or nature? The title may sound like Surrealism or science fiction, but it also looks suspiciously like self-portraiture. It does, though, allow Firelei Báez to float amid flowers. And is that a furry black bear beside her? A living landscape need never be a universe of one.

Paul Paiement ran at Ethan Cohen through November 23, 2024, Hilary Pecis at David Kordansky through October 12. "Shifting Landscapes" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 1, 2025.