Over the Top

John Haberin New York City

Chelsea Gallery-Going: Fall 2004

Sure, the torrent of shows each fall has to feel overwhelming. Those weeks after Labor Day, as group shows slowly give way, are the gallery-goer's Indian summer. And then, just when I think that the surreal calm and warmth of a New York summer might extend forever, there it is: the cold, hard fact of Chelsea's continued expansion, amid the global art world's unending day at the mall. And there it is, too: the outsize scale of installation art, the sheer volume of video art, and the unruly mess of art today, less described than accepted as pluralism.

This fall, however, the intensity came with an even greater shock, for it seemed to find its equivalent in the work itself. Artists have gone so consistently over the top that it could already pass for the latest paradigm. Consider such old-timers as Georg Baselitz and Julian Schnabel alongside Will Cotton and Bjorn Melhus, Sam Taylor-Wood, Julianne Swartz and Devorah Sperber, Jonathan Cramer, and Jane and Louise Wilson.

American beauty

This scene makes far too many artists work on the realization that far too many viewers, pressed for time, will stop only when art works far too hard to force the issue. It makes sense, then, that two old rebels are back, in 3D. Both present themselves as sculptors, with oversized totems in oversized galleries. If it sounds as if art has stumbled onto Easter Island, has Postmodernism become an extinct culture?

George Basilitz erects large statues, but their roughly hacked wood goes along with his love of folk imagery and German cultural traditions. The subjects, mostly women, recall, too, the curiously idyllic spirit behind the apparent irony of his painting. Turn those old canvases right side up again, and one would see pleasant enough people in rural surroundings. The combination of lyricism and violence in representation may evoke Willem de Kooning, but it has me longing for that good old American mix of egotism—and at least a minimal sense of humor.

Julian Schnabel has both, if not de Kooning's unstable spaces and complex feelings. The tall constructions, like Schnabel's paintings, throw in anything from used parts to stuffed animals. They turn statue into collage much as he has done with canvas. They also look unfocused, even forlorn, somehow suiting an artist with big ambitions but an ever-shifting career. Maybe he can use them as the set for another movie.

At Mary Boone, the gallery that once represented Soho's next wave of decadence after Schnabel, Will Cotton is up to his usual pink and white photorealism. The canvases represent women and cotton candy, but if that makes you think of a socially grounded narrative, in which a man has remembered to bring flowers, you must have checked your postmodern credentials at Mary Boone's door. The large scale and close vantage point cut off any sense of space and context. They make his subjects equal objects of delectation. If the metaphors seem obvious, Cotton is enjoying it all as much as the next guy—or, more likely, a good deal more. It makes perfect sense that Mark Shetabi, part of a group show in Brooklyn called "Squint," represents Boone's space with a peephole.

If art like this seems truly over the top, one has to expect that in this effete center of decadent America, right? Well, take heart. Bjorn Melhus, too, finds America's impulses writ large. His work could well have been designed by Islamic Jihad for its new prime-time slot on Comedy Central. Picture tubes cover two walls, and five more old television sets come stacked in the opposite corner, like Brancusi's Endless Column refracted through daytime TV. That leaves just enough space for a large wall projection.

The sounds and images pulse madly in and out, all from Jerry Springer himself. A low platform in the middle puts one in the studio audience. However, its bareness, not to mention the volume of clichés and their dispersal in space and time, make one more a knowing observer than an on-stage participant. In "The American Effect," the Whitney's show last fall of artists from overseas revisioning America, Melhus relished that combination of total immersion and safe distance. There the overlay of sounds, from different sources, made it hard to pin anything down. Here he wants it to be easy, but only because he is definitely not changing the channel.

More in sorrow

One sure way to go over the top is to offer a bad theatrical performance. Another is simply to float above it all. It will hardly surprise anyone that Sam Taylor-Wood goes for both. She calls her latest exhibition "Sorrow, Suspension, Ascension," and visitors may well leave, like the ghost of Hamlet, more in sorrow than in anger—but not much closer to heaven.

Wood's usual aims could almost sum up the Young British Artists—or even some younger ones. She tackles heavy themes, such as sex, death, and religious transformation. She also presents them as high theater or a fashion shoot, with herself and a celebrity circle the star performers. At its best, this has the potential to shake an audience while forcing it to question its vulnerability, whether to quick conclusions or to envy. Just as often, however, it comes off as simply overwrought and self-involved.

In Sorrow, a densely hung wall of photographs shows actors pretending to be on the verge of tears. Naturally that means prominent actors. Again, her concerns cancel out. Had she used professional models, they might, given a little luck and a lot more emotional insight, have collided head on. Behind that wall, Suspension plays with the rest of the gallery's large, central space.

She seems to catch herself in midair, diving athletically, gracefully, and dangerously within a wide, pristine studio space. The studio's loft windows open up the gallery walls to the artifice of natural light. Yet, again, the unbending focus on herself leaves the work abstract and obsessed with its own fame. One can all but hear her smirking at how easy computer superposition is, especially compared to the results of her professional trainer. When Rosemary Laing floats through the sky in feathery dresses, at least the Australian photographer situates her fantasy in expectations about femininity and about her native land's open country.

Art like this relies on heightened signs of sophistication to lend depth and credibility to the obvious. Yet it leaves me thoroughly dispirited and thoroughly used. One does not even get to complain that one saw it all the moment one walked in the room: having seen it all is precisely the point. Oh, did I remember to say that America is decadent?

In a video alcove, a lean young man, dressed well enough to sit behind the desk at Mary Boone, tap dances above a prostrate body. A dove rests on his shoulder, finally checking out of the scene as the dance of Ascension comes to a stop. In Woody Allen's Bergman parody, a knight plays gin rummy with death. In the better parts of London, apparently, the knight puts on evening wear and tap dances. I must remember to hire him to play me in the sequel.

Pipe down

Visitors to an exhibition of Julianne Swartz overlook something: unlike Pipilotti Rist the same month on video, she is not creating an installation. For once, in an age of the more the merrier, that signals actually a weakness.

Swartz made waves at the last Whitney Biennial—sound waves, in fact. Her thin, clear piping snaked down the stairwell. Up close, one could hear "Over the Rainbow." Remarkably for a sound work, it hinged on both its physical layout and, at another extreme, its faintness, close to evanescence. Remarkably for sculpture, it truly drew on in to listen and to decipher and yet, just as much part of its intimate relationship to its space, remained easy to overlook. Remarkably for an installation, its industrial or laboratory appearance drew the Whitney's imposing architecture back into the modern world.

In short, it remade the parameters of Minimalism for an era of pop culture—of recycled film stills, only hardly so still. Up close, however, something important vanished with the sound. Swartz challenged me with no particular associations between Madison Avenue and Kansas. Not even Judy Garland wannabees would linger to hear that much more. My mother and Liza Minnelli did not so much as bother to show up.

Swartz's latest conveys an even greater sense of wonder—and the same yes, but. More tubing makes elusive patterns out of its right angles. The pleasure is visual rather than audible, and so is the savvy encounter with the space. Peeking in one end of each work, one might find anything from one's own reflection to the movement of another visitor—or nothing much at all.

Will her works go beyond turning gallery-goers into kids with their first kaleidoscope? Should it? Collectively, it transforms one's experience of the gallery despite itself. Now if only people stopped checking out each work, smiling, and taking it all in stride.

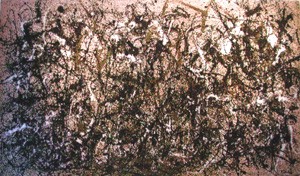

After all that piping, ready to say pipe down? What could be more over the top than to tackle one of Modernism's most troubling personalities, not to mention greatest painters? How about when it involves creating a single image from 165,000 pipe cleaners? When Devorah Sperber, again in the "Squint" group show, does a halfway reasonable facsimile of Autumn Rhythm—if reasonable makes any sense in this context—she deserves at least an admiring smile. Sure, Nancy Drew has already done her replicas of the period in felt and glitter. But Drew never brings back warm memories of those pipe-cleaner men I made when I was five years old.

Pollock on video

If taking on Jackson Pollock with pipe cleaners sounds dangerous, imagine trying it with paint. Where once painters felt that they must, emulation now may well seem an anachronism. Still, what could be more contemporary than an anachronism, now that artists go to school and everyone copes with a loss of history?

Jonathan Cramer takes the gamble. One canvas has a sharp vertical division in dead center and plunging, vaguely humanoid outlines that make me think instantly of Pollock around 1942 and 1943, the intense years bridging symbolism and abstraction. Flowing paint holds together the spatter. Others have vaguely eye- or leaflike motifs that would be at home with Pollock or Lee Krasner. If he outdoes them in scale, with a single work spanning several walls, perhaps one has to go to extremes just to achieve the strangeness that a mural scale had back then.

If I had any doubts about the echoes, a thoughtful handout, written by Amy Golahny, describes Cramer's work as an ongoing "debate between linear and painterly." Golahny refers to Renaissance rivalries between Venetian light and Roman form, before herself placing Pollock in the painterly camp. It pays to remember, however, how much the very debate helped to define Abstract Expressionism. Drawing in paint seemed then like a resolution. Indeed, it may pay to remember how geometric abstraction from the 1960s, which may seem in the opposite camp, sought its own resolution, too. Frank Stella in his symmetry breaking, Ellsworth Kelly in his identification of form with the picture plane, Brice Marden in his lush opacity, or Robert Ryman combining of all these seemed once far different from prewar geometric composition.

Cramer, however, is ahead of his critics. He starts with underdrawing, as Golahny notes, often in perspective, progressively superposing architecture upon architecture to create "a world of violent activity." I frankly had trouble discerning the representational or grid-like layer, and sometimes the violence amounts just to derivative shapes and gaudy colors. I had no trouble, however, admiring how well Cramer emulates an older art's perpetually evolving compositions. He has that command of scale that invites one to approach up close. In moving physically past the work, one participates in its temporal evolution and the temporal evolution of one's perception.

Even on a second visit, I left moved by his ambition but uncertain how well he pulls it off. At least a side room convinced me he understands what lies at stake.

His video shows a grid evolving into an abstract composition and dissolving again into black and white. It could pass for one of those reductive lectures on how abstraction really works, but it manages to bring painterly metaphors into the video age. It reminds me that, in an age of video games and no-smoking areas, Sperber calls her pipe-cleaner units pixels. It also reminds me that sticking Cramer's rancid yellows into a composition takes risks.

Second thoughts

With all these, think of the Neo-Expressionism of twenty years past, only without the pretense of a few lone geniuses. Besides, artists today have no dogma, neither high-modern ambiguity nor postmodern irony, against which to rebel. When David Altmejd the same fall plays rebel, he naturally plays a werewolf. He could be a character in a teenage zombie picture.

All these, too, have me reconsidering Chelsea's diversity. Could the death of the avant-garde allow for multiplicity? Or could it mean drift? Imitation of pop culture is not always the highest form of flattery.

Jane and Louise Wilson also have me reconsidering matters, and my second visit to their latest exhibition came as no accident. I knew I had not made sense of things, and it nagged at me. Should the work have made sense—and does that matter?

The video covers multiple screens, arranged floor to ceiling in hollow cubes, like a hall of mirrors that fail to reflect. One could mistake the shots down long, empty halls for the setup in a horror film or a somber documentary of failed institutions, like a tedious version of Frederick Wiseman's Titicut Follies. And indeed the Wilsons shot a mining town and sanitarium in New Zealand.

But is sadness enough, without Wiseman's incisive sense of people and place? Conversely, is the imagery too obscure, too in need of a press release? And what are those legs, like an exercise class or a chorus line turned sideways? How do sensuality or feminism fit into the unoccupied space between past and present?

On second visit, the creation of a new space became overwhelming. The title, Erewhon, refers to Samuel Butler's novel, as if to make Michel Foucault's point about madness as a creation of oppressive utopias. I thought, too, of a literal nowhere running backward. Perhaps I can see the legs as additional observers, finding their own place in it all, amid the redoubling of screens and experiences. For all fall's ridiculous extremes, perhaps I should see Chelsea that way, too.

George Basilitz ran at Gagosian through October 30, 2004, Julian Schnabel at PaceWildenstein through, Will Cotton at Mary Boone through October 29, Bjorn Melhus at Roebling Hall through October 16, Sam Taylor-Wood at Matthew Marks through October 30, Julianne Swartz at Josée Bienvenu through October 16, Mark Shetabi and Devorah Sperber at Jack the Pelican as part of the group show "Squint" through October 17, Jonathan Cramer at Remy Toledo through October 18, and Jane and Louise Wilson at 303 Gallery through November 6. A related review picks up Julianne Swartz in 2018.