Bottoms Up

John Haberin New York City

Georg Baselitz

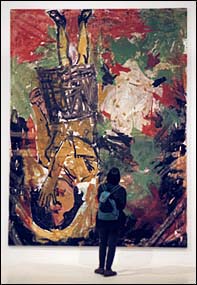

Some twenty-five years ago, Georg Baselitz helped turn the art world upside-down. The German painter's large canvases quite literally stood on their heads for attention. Now his retrospective makes cultural trends all the harder to pin down.

Baselitz rode into town on a much touted wave of Neo-Expressionism. The wave must have rolled over me too: I recognized at least one group of his gaudy figures a quarter century later. It came among the first of many "neo" movements, and the loaded prefix added an unsettling nostalgia to Modernism's shock of the new. It looks somewhere between escapist and just plain confused. Yet something in art had changed.

Acrobats and heroes

I looked again after so many years at those very same nearly featureless men. They stare open-mouthed, arms pressed closely against distended faces. Arranged behind a table as if for the Last Supper, their looks and upraised gestures could belong instead to a crucifixion. Are they shocked—or just painted broadly in harsh yellows and reds? One can hardly say for sure. Try deciphering a tavern scene for which the operative phrase is truly "bottoms up."

Georg Baselitz hit the big time after a decade dominated by geometric abstraction. The art world had shown that it could absorb almost anything, from random drips, rock piles, and soup cans to interminable videos. In all that, artists still reflected on their craft. And in all that, critics still puzzled out its assumptions. In America, only the master of comic disdain, Philip Guston, could muster the arrogance to object. Surely art had nowhere to go but up—toward a heaven of controlled experiments in oil.

The outsider remained, but in Europe. In Germany and Italy, the modern era had been physically and even emotionally destroyed. This new Europe could parody its history, but it could wrest its future only from America. Since then, other artists have made any gestural painting look quaint. Talk about "shock art," misleading as it is, fairly suggests all the confrontation of German Expression and the black paintings of Robert Rauschenberg combined. In looking now to Neo-Expressionism, give credit where credit is due.

Baselitz's stark-yellow dreamers, turned legs skyward, seemed just the thing to disturb arcane formalism. They gave art the air of a bad amateur carnival. Yet their sheer size derived from Abstract Expressionism and Pop. They would have been inconceivable without the success of postwar American painting. Their very display required the recent conversions of old loft districts into public spaces. The heroic scale and masculine subjects also recalled American myths.

After that, though, any resemblance to high Modernism and its subtle geometry was purely incidental. Abstract Expressionism had taken the solid primary colors of classicism and blown them up to poster size. Pop Art had cooled things off still further. Baselitz and his peers, in contrast, took their shrill colors from German Expressionism, perhaps in the bulkier allegories of Max Beckmann, Beckmann in New York, a Beckmann self-portrait, and "Degenerate Art." Their motifs too—wide-eyed drinkers and bulky, striding peasants—trace back beyond late Modernism. Only the figures' solitude and incomprehension would look strange next to depression-era bar scenes by George Grosz.

With their messy surfaces and trademark style, Neo-Expressionists seemed to dare canvas to live up to the artist's own dimensions, and they still do for Albert Oehlen and a younger generation in Germany. For Meyer Schapiro, the critic and historian, those who consider abstract painting inhuman must "underestimate inner life and the resources of the imagination." Here art conventions were held up to the resources of one man's imagination—and found wanting. No wonder that, in curating drawings, Baselitz has paired himself with a Mannerist. Then too, the artists had the temerity to reintroduce representation and overt feeling. And Baselitz's trademark images were indeed standing on their heads.

Conflict and condescension

The inversion marked a resistance to overt narrative traditions. The "art spirit" and an artist's emotional distress had grown too much more important. Fine painting, long centuries had taught, resembled a mirror or a lens, devices that reverse an image. Normal perspective heightens the ordinary viewer's subjectivity, but also calls attention to it and demystifies it. With Baselitz, in contrast, no one can escape the quirkiness of an artist. No one could escape, too, the lens-like inversions of his human eye.

In fact, he was surely enjoying himself royally. Here thankfully was none of the shattered ego of prewar Germany. The painting even looked like a carnival stunt, a metaphor that Curtis Talwst Santiago and others take more literally. But was his work about the recovery of subjectivity after Modernism or about the failure of the self? Who was to choose among all these interpretations? And who was to judge the depth of its seeming rebellion?

The retrospective raises the tough issues afresh, in part because it offers a long look at Baselitz's early career. His rebellion against abstract painting and narrative began over a decade before he made it big. So did the outsized crisis of his ego. His first upside-down man dates to 1969, and works since 1962 have been entering European museums. Here at last one can see them as a group. And that means facing up to their insistent banality.

A long early series shows lone figures striding clumsily forward in a cramped, indefinite space. All are men—and worried about it. Some flaunt their overblown pricks. Others wear camouflage, as if it were safer not to stick out among the trees. Culture, it would seem, had better not defy nature. Culture just happens to include the painter, too, and nature is traditionally female.

The conflict surfaces even more obviously when Baselitz turns to sculptures of women. He hacks huge totemic heads fiercely out of wood. I imagine an artist unsure whether to revere or destroy them once and for all. As I returned to the later paintings, I never got over the echoes of shallow male posturing. Women still appear rarely, right-side up amid the general chaos. This is just not their problem.

I found it harder than ever to avoid my perplexity at what the art really means. How much of his irony is halfway conscious? How much of it is felt pain and how much empty condescension? It is typical of Baselitz's slightness that I can offer no easy response. It hardly helps that work of the last few years repeats earlier imagery again and again. Even the artist's crisis has come to lack a clear focus.

The postmodern carnival

Without Baselitz and his media moment, the whole idea of Postmodernism might well have made less sense. Within months of his arrival in Soho, Americans joined the party, making the new claims obvious. Julian Schnabel in 1983 substituted broken saucers for paint strokes. Nothing, it seemed, could recreate the artist's titanic image intact. Neo-Expressionism was surely not the first art movement to become a media event, but the art market had grown more sophisticated. That is a real tribute to German painters like Sigmar Polke or Baselitz, but it also makes him—and the recent scene—more disturbing.

His breakthrough was suspiciously timed. Minimalism had already become profitable, and younger artists had long given up looking for lofts in Soho. For the first time, one could no longer comfortably get through all of its galleries in a day. Chelsea lay well in the future, but Postmodernism had begun, and the revolution was curiously painless. Minimalism had looked so very plain, but it came with enough verbiage to choke a culture, as it indeed hoped it might do. The new (or Neo) art looked accessible, but it could hardly be bothered to linger for an answer.

One should not press this art too hard. It works best as unexamined gesture. It allows one to agonize in living color over things without feeling hurt. For once in art history, who needs interpretation, not when a star is suffering in the public eye—and having too good a time doing it? I wanted to show my respect for its overturnings by doing handstands all the way down the Guggenheim's ramp. At the very least, I could have brought a mirror.

Baselitz may also not show to best advantage. Since its restoration, the Guggenheim has coped with the ramp in perhaps the only way possible: the museum has moved painting into the newer wings off to the side. Now stuck with a painter in the main space, the curator has to hold him down with plastic supports affixed to floor and ceiling. These canvases were not meant to hover in midair. Like the figures, they might easily fall right over if one gets too close or thinks too hard.

To see why Baselitz has had to cram himself into the ramp, one has only to step off into the Guggenheim's newer, more traditional exhibit halls. (As it happened, they were showing the quiet squares of Josef Albers, almost like a rebuke.) Even his largest paintings get lost in the topmost rectangular gallery. They look all too anxious against its long, even wall and its quiet window over Central Park. In the end, though, I had to wonder what would have become of Postmodernism without them. Could one have seen more clearly a continuity between past and the present?

One might have seen better the low-art tactics and political thrusts in Modernism all along, and one might have had to reassess the ardor and irony of the best Postmodernism itself. The art world would certainly have latched on more quickly to other, better European artists, such as Gerhard Richter, Richter's photorealism, and his argument with Germany's past. Postmodernism introduced to art and philosophy a special awareness of their history. How strange that it depended so heavily on historic accidents. Postmodern also wears its irony on its sleeve. How strange that it needed the glib but sincere entertainments of a magnificent but capsized ego.

Georg Baselitz ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 17, 1995. A related reviews looks at Baselitz drawings.