The Naked and the Old

John Haberin New York City

Gallery-Going: Chelsea in Winter 2001

Ever have one of those days when you just have to see some good old-fashioned art? These days, it seems, the whole art scene is having them.

I have days like that, too, of course. They get me out to museums even when I would just as soon hide inside behind this virtual reality. They get me over to Chelsea galleries after another bad night, when I only dreamed that art still has the power to raise nightmares.

In fact, art seems desperately nostalgic at the moment, and that may account precisely for its easygoing air. Even a quick look around should end on the increasingly old-fashioned visions of Nan Goldin, Robert Longo, and Lisa Yuskavage. A postscript brings the last of these up to 2006.

Art after the end of criticism

Critics love to look for pluralism. Proper leftists like me may count it a moral imperative. As in any other business, and art increasingly is like any other job, inclusiveness redresses past wrongs and defines a more open society. By foregrounding race and gender, it also makes one see things one had not seen before, just as art was supposed to be doing.

Conversely, pluralism can sound a lot like globalization. It could stand for the ultimate triumph of the art market in an era of perfect circulation. If anything can turn into art, and all too often anything does, galleries can open anywhere, without losing their power as arbiters of the day's taste. Museum directors can claim their power of "making choices," as a millennial survey at the Modern puts it. Even the Modern's alternative space out in Queens, P.S. 1, made "greater New York" into a kind of citywide art shopping mall.

Either way, art seems to have triumphed once and for all, at the price of having nowhere to go. "Art after the end of art," Arthur C. Danto called it. Could art really have escaped its own history?

Yet something is missing from this picture, and it could well be art. For each perspective here, art's success counts as an escape from history. Indeed, it sounds like an escape from human limitations altogether. Racism, sexism, or Modernism, out they go, and fine art survives, having transformed forever what Danto calls "ordinary things." Even the lines for blockbusters need not count as a limit, so long as one can purchase advance tickets online.

Something is wrong here. Why do the perspectives, of left and right, remain entirely at odds? And why do artists spend so much time looking back? Have they really found the end of art history, or just of historically aware art criticism?

On a single day in Chelsea, artists must have grown nostalgic in a hundred ways. They dwelled on old movies and ballet from old Russia. They lost themselves in the comforting light of childhood and painterly realism. They took Freud's fascination with memory back to Vienna. They even got nostalgic for transgression, with seedy family portraits, female nudes, and a look back at the East Village art scene.

B movies, ballet, and bitter memories

All too often, nostalgia is bound to come off pretty silly. Vernon Fisher throws up scenes out of an old Robert Mitchum movie as if the mere mention of film noir guaranteed authenticity. Karen Kilimnik bathes her doll ballerinas in soft lights and music. Just in case the classics fail to carry enough charm for yuppies, Kilimnik's dancers also include Diana Rigg at her tightly clad, karate-chopping best. Oh, sure, I know to look for irony, but that, too, must come with more than a hint of nostalgia.

No wonder so many shows have had a fascination with childhood. I saw way too many knowing combinations of toy parts and big buttocks. They floated along the wall, above painting and photography. They helped artists to merge childlike drawing and flip, adolescent words. Let me not even name the perpetrators.

Leonardo Drew does better, covering vast gallery walls with his toys, spools of thread, and rust. The dark canvases look back to Abstract Expressionism's ambitions and Arte Povera's surrender to time and decay, as with Giuseppe Penone in wood and water. Perhaps those movements have been gone too long, perhaps Drew has painted in rust for so many years that he can only move on (as I discover with Leonardo Drew in 2024), or maybe Hollywood has tainted anything larger than life. Somehow, though, his wish for grandeur now carries more than a whiff of escapism. I wanted something of Abstract Expressionism's structural rigor in his small cascading squares—or more of Arte Povera's gutsy modesty. I even wanted somehow to escape the past.

Realism necessarily comes with a sense of loss, especially when it announces itself heir to Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman. Dona Nelson's landscapes look like details from the Hudson River School. I found them modestly appealing, but she blows them up just enough to lose focus. If that were not enough to heighten the pretence of Romanticism, she adds titles out of 1950s abstraction.

Can I wax nostalgic even for cold afternoons stepping over drug users? If it means more memories of a search for art, one gallery deserves the chance to help me try. Pat Hearn died last year, and her gallery is offering a several-part tribute, starting with her years over past Avenue C. I cannot promise that I care any more today about George Condo, Condo cartoons, or Phillip Taaffe's psychedelic abstraction. I have qualms, too, about her opportunism in celebrating the Village as a community, then picking up for Soho and again for Chelsea, about as soon as it made financial sense. Still, I shall cherish the list of her addresses and shows from those years. I get nostalgic for my past, too.

Like Hearn's heirs, some frankly deserve the chance to look back, even when that means looking back on AIDS, masturbation, and sagging flesh. Nan Goldin has pursued one project for years now, and the frank accumulation of memory carries far more emotion than any room of her photographs ever can. Her insistence risks stagnation, but one can see its power in such photographers as Donna Ferrato, and it also helps me as her viewer get past that stress on the seamy side of life. She dwells on people as intimates, whether her friends and their kids or herself. Do they come off uglier than they deserve, in their bathing suits and other states of minimal clothing? Yes, but intimately human as well.

Pluralism as nostalgia

Look back at claims to pluralism and the end of art. Such current wisdom about Postmodernism has it wrong. Precisely because anything can be art, one must start to see it historically.

Perhaps art no longer has a historical imperative. Perhaps no school can promise ultimate truth. Perhaps one can no longer speak of "the triumph of American art" without hating someone—whether corporate America for capitalizing on that success or the Young British artists for taking it away. That only means, however that one can no longer step outside of history, as if art's second coming had taken place. Danto can see "anything can be art" as a logical truth only because his philosophy defines art itself analytically, apart from "ordinary things." In fact, logic went out the window, and art started to recoil in fear of the ordinary.

At times in the last century, criteria for art and formalism went together. Why not? Both sought a conscious escape from historicity, just as they did from the deadening American culture that surrounded them. In contrast, once art took on the task of reflecting consciously on the past, it had to spell chaos. Once artists could no longer hope to debunk art once and for all, they freed reflection on the distinctions each new attempt makes, and thus the nostalgia known as pluralism. For the first time in decades, even painting, thank goodness, is legitimized.

Appropriation and politicized art alike freed up pluralism, but only by looking backward in their different ways. Appropriation reinvented itself , taking into account first Dada and then 1980s appropriation, while politicized art reflected increasingly not just on history, but on art's very place in politics—and the very place of politics in a culture's history. Postmodernism thus sustained itself by a continued attack on Modernism, long after the battle would seem already to have been won. The result gave the modernist impulse a fresh validity in its own continued dismay at the present.

This carries with it risks. Just as nostalgia is a cheapened form of memory, an extended attack on the past can be a cheapened form of rebellion. Caught in between them, art's pluralism may have nowhere to turn but in circles.

Consider in a little more depth just two more shows by art-world stars. Both take epochal social change as subject, and both hide it behind a surface so ordinary one could mistake it for the realism of art's past. Both badly cheapen art's history of craft and rebellion, and yet I still hate to dismiss either one. Both know how to push easy buttons, and still I fell. For both, too, though, I know how shallow are my fears and sympathies. The paradox could stand for the nostalgia with which Postmodernism has continued to battle its past.

Freud as centerfold

With his softness for the past, Robert Longo took me even more by surprise. Here I had that so trendy figure of the 1980s, so properly postmodern for abandoning abstraction and Minimalism except as an oblique reference to modern life. For Longo, painting became an installation with a laconic, socially sanctioned subject. Yuppies leaned over in thought and flailed on the dance floor as if a Tribeca lifestyle amounted to existential torture and a study in identity. I fell for them, but the message has grown as shallow and stale as the subject he once tore apart.

Now, after a turn making films, he has recovered belief in drawing and even Modernism. One could easily mistake the charcoals, with the titanic scale and political edge like that of Melanie Baker, for aging photographs of a departed European world, lost in reflections and shadows off long-forgotten things. But read these titles. Longo has literally discovered his Freudian unconscious—the famous chair, the Egyptian antiquities, the doorway with a swastika above to scar forever its Viennese aura. They make Longo's journey into the mind a kind of package tour of art's past as well.

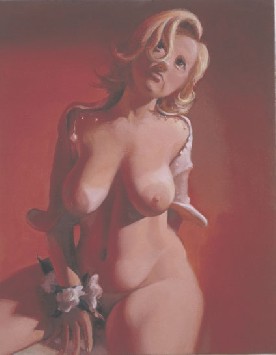

The same simple pleasures define Lisa Yuskavage. At her worst, paintings fall somewhere point between soft-core porn and greeting cards. At her best, though, the combo allows her the trendy topic of female nude with a self-conscious nostalgia for art before Modernism, realism and Surrealism included. The idea got her and John Currin, an old Yale classmate, plenty of press leading up to the last Whitney Biennial. Now they have earned her both a show in Chelsea and an oddly premature retrospective over on, literally, the wrong side of the tracks. It lies just a few blocks from Philadelphia's Amtrak station, at the Institute for Contemporary Art.

Yuskavage's subjects range from a frowsy thirty-year-old to a naive twenty-year-old, depending as much on how she catches the light as on reality. Half asleep, her wispy hair all the blonder for the saturated light, her fragile build all but shouting vulnerability, she inspects her private parts as if she had stumbled on them for the first time. Her inhumanly rounded breasts show definite signs of arousal, but her face does not. Is this innocence or experience? Playboy poses the same alternatives, but then so did William Blake. They recall a time when ambiguity meant more than not having a point of view.

Should you buy her as a deep explorer of gender and a great realist? Only a few years ago, she, too, had not yet discovered private parts. She stuck up heads in the same exaggerated light, with hairdos and Barbie features right out of some department-store window of the disco era. After a turn at surrealist figures draped in rigid clothing, she hit on full-figured nudity as if by chance. It may make you long for Robert Mapplethorpe and Mapplethorpe portraits with their love of style and Pierre Molinier's bitter humor. Yet she genuinely speaks to an age that longs for a past against which to struggle.

Some day, one may be able to look back on all this mess as among art's dullest and most frightening eras, Modernism's own late Baroque. Worse still, one may never be able to escape it enough to look back on it. In that sense, art may really have reached an end. Yet one will also see it as engaged in fond recollections and hard-fought battles. For all her shortcuts, Yuskavage is among its most ardent fighters. At least for now, that will have to do.

Drip, drip

When I first saw her work in the galleries, at that Whitney Biennial, and in her midcareer retrospective, I hardly knew which version to admire or to criticize. When I saw her again, after Currin, too, had a museum imprimatur, she seemed to have gambled on undermining reality and won. A more consistently natural light, a more consistent emphasis on older, less-ideal women, still more nudity, and close-ups that brought out their anxiety managed to confront me both with my desires and my empathy, demanding of me which I should trust. Everything that I wrote so solemnly in the preceding paragraphs seemed lame.

Perhaps she heard too much praise similar to mine, for in 2006 she confronts me with my own newfound sympathy. The light has grown more syrupy than ever. Perhaps it drips from those pomegranates and other suitably curvaceous fruit that her woman now attract. It pervades, too, paintings within a painting that may or may not be half as simple or hers. The artist's eye draws back, revealing more drapery, more awkward poses, and ill-defined spaces. All, of course, look stranded in her part of Zwirner's outsize galleries, now stretching almost half a Chelsea block.

Have greeting cards won out over feminism or art school? Perhaps, but the cards celebrate a happy occasion that does not often make it into Penthouse. She is painting pregnant women, and it shows her continued strengths as an illusionist that a friend wondered if she herself were not expecting. The illusion goes against all conceivable visual cues. Does that make it less true or more emotional? I have no idea, but I admire her for deceiving me.

Vernon Fisher's "Angel Face" series ran at Charles Cowles through February 24, 2001. Karen Kilimnik ran at 303 Gallery through February 10, Leonardo Drew at Mary Boone through February 10, Dona Nelson at Cheim & Read through February 17, Part I of the Pat Hearn memorial show through January 10, Nan Goldin at Matthew Marks, the 22nd Street space, through February 24, and Robert Longo at Metro Pictures through February 24. Lisa Yuskavage had both a show at Marianne Boesky through February 3 and a small retrospective at the Institute for Contemporary Art of the University of Pennsylvania through February 9. Her 2006 show ran at David Zwirner through November 18.