When Spring Runs Late

John Haberin New York City

Summer Sculpture 2019

Alicja Kwade, Carmen Herrera, and Leonardo Drew

Put it down to a brutal winter. More than ever, everyone's eyes were on the calendar. Was spring running late? Art stepped in, with a reminder that the cycles of the heavens would reassert their force.

I look forward every year to sculpture on the roof of the Met, for that long-sought confirmation that Central Park is once again green. You may look forward to the rooftop bar in summer, for a cool breeze, the sweep of the park, and of course a drink. This year, we may both be disappointed, for hedges all but bar the view.  I know I am, but that may yet have its compensations. One can appreciate instead one's place between a landmark museum building and the sky. Alicja Kwade makes it her place, too, with an enormous astrolabe.

I know I am, but that may yet have its compensations. One can appreciate instead one's place between a landmark museum building and the sky. Alicja Kwade makes it her place, too, with an enormous astrolabe.

Soon enough, Socrates Sculpture Park followed, with Kwade herself a contributor. It makes the East River waterfront in Astoria "a gateway to the galaxy." Art, it seems to say, can do no less. Posts the next three days continue a 2019 tour of New York summer sculpture. A final segment runs all the way from Harlem to City Hall for Carmen Herrera, ending with Leonardo Drew in Madison Square Park. Separate reports take up Siah Armajani in Brooklyn Bridge Park and Frieze Sculpture in Rockefeller Center.

In orbit on the roof

ParaPivot at the Met consists of two sculptures, each with an eye to the heavens but a place apart on earth. Past summer sculpture on the roof tends to cry for attention like Huma Bhabha last year, to take over the joint like Mike and Doug Starn, or to abandon it to the bar crowd like Pierre Huyghe. Alicja Kwade allows one to circulate freely without losing awareness of something larger than life. Steel frames cross one another at odd angles, like drawing in the air. Each creates imagined walls while remaining open to the sky. Each also contains spheres of polished stone, about the size of a basketball and a lot harder to move.

At her gallery this spring, a work has three frames and three rough stones—one resting in a lower corner, another wedged tightly between two frames, and a third draped over the top as if sagging under its own weight. At the Met, the stones have variegated colors and a uniform shape, like the planets as seen from space. They draw one's eye into space as well. Everything sits stock still, even as the frames seen to pivot with one's shifting point of view. Kwade compares the work to an astrolabe, an old device for charting the solar system relative to the horizon. Born in Poland and based in Berlin, she may identify with Nicolaus Copernicus at that.

Copernicus, the Polish astronomer, overturned the medieval universe by showing how the planets orbit the sun. For the Met, Kwade, too, "calls into question the systems designed to make sense of an otherwise unfathomable universe." She has appeared in a show of "A Disagreeable Object," and she loves measuring devices that fail to measure. Also at her gallery, large works on paper start with a random array of black vertical marks, add less regular traces, and end with the shorter and thinner marks alone. The verticals are the divisions on a measuring stick, while the others are hands from a clock. They could be marking time or losing count.

Still, Kwade seems too massive and lyrical for the cruelties of deconstruction. She is also nostalgic enough to have nine planets at the Met, as if Pluto had not yet suffered a demotion. She thrives on contrasts—between sculpture and space, mass and light, and matter and motion. She reflects, too, on art as a human construction amid the course of nature. At the gallery, she carves out a bar stool and a coat rack from standing tree trunks, as if she could not be bothered to cut down the trees before finding a common space. Sadly, the bar stool cannot join others on the Met roof.

In one last work at the gallery, she becomes an illusionist. Kwade, who has also worked with shattered or sliding mirrors, sets out large stones on the floor, separated by sheets of mirrored glass. As one walks along them, they appear to morph successively into one another. They also progress from a rusted steel block to an elongated sphere. Once again, she evokes vision, mass, and motion. Once again, too, she hints at regular solids and an orderly progression, even on earth.

Simone Leigh takes another step into the air. The self-affirming bust of a girl looks down from a new "spur" on the High Line crossing Tenth Avenue. Others will have to settle for "En Plein Air," the term for painting out of doors to capture the light. Not that Claude Monet becomes less of a plein-air painter by display in museums—or a duller artist any more of one for display up on the rails amid condos and landscaping. Few here even look for a middle ground between painting and sculpture, as opposed to layered abstractions by Ryan Sullivan or a ruined palace by Firelei Báez, in tribute to Haiti's tortured history. Sam Falls does paint seasonal vegetation on the four rectangular frames of his "arches," Daniel Buren comes closest to that middle ground in converting his plain stripes into pennants fluttering proudly and colorfully overhead.

Looking up

I made it to Socrates Sculpture Park after days of record cold and heavy rain. I had to look down to navigate deep puddles and treacherous ground, while leaves and branches rippled in the wind. The artists in "Chronos Cosmos," though, have one looking up, to what the show's subtitle terms deep time and open space. Of course, the Broadway billboard over the park's entrance always has one looking up, and Oscar Santillán shows a sunrise over a sooty earth. Within, Radcliffe Bailey draws one into a tapered silo, its roof open to cast a broad field of sunlight on the wall. Comforting music takes on "Afro-futurist" rhythms.

In reality, they are looking both inward and out. Alicja Kwade turns up again, as a summer double big dipper. Here she regularizes her rocks pierced by steel arcs so that they form circles, like electron orbits in early models of the atom. Santillán may seem to have in mind the neighborhood's industrial past—but he took his photograph in South America's Atacama Desert, a home to cutting-edge telescopes, after melting and polishing the desert sands into a lens. He is working from the ground up. As for Bailey, he compares his sculpture to both a space capsule and a bunker, and he suspends a shell from the ocean floor overhead.

Few of the park's group shows have been this coherent. If Kwade has an interest in early modern astronomy, MDR (in real life, Maria D. Rapicavoli) fashions a telescope from alabaster, found in Galileo's Tuscany. Through it, one sees a fantastic city with echoes of the real one across the river. And if Bailey has his rusted steel and sunlight, so does Beatriz Cortez for pyramids with gears powered by a solar panel. Heidi Neilson directs her Moon Arrow at the moon, even when it is on the other side of the earth. William Lamson calls his construction Sub Terra.

One has to take a lot for granted, quite apart from the science. Miya Ando welcomes the wind, with black fabric suspended across a dozen steel gates. Its long, gentle curve references the Mayan calendar and the solar year, while its points of white represent stars. A Japanese sky god, she explains, created the Milky Way in frustration at his daughter, whose tears supply summer storms. Well, fine. Lamson's scaffolding holds concrete stalagmites and water catchments for the "long percolation of geologic time."

Alternatively, just take on faith the reviving power of city parks and the Manhattan skyline. Eduardo Navarro takes them all for his Galactic Playground. Its concrete riffs on real playgrounds, while its hexagon of seven colored bands riffs on ROYGBIV. It also serves as a sundial, with a pillar at center to cast the shadow. In place of numbers, it has verses, with a message beyond the time of day. "Multiply the age of the sun by yours," says one, leaving you more than enough time to observe and to play.

Harold Ancart brings a handball court to Cadman Plaza. Maybe the nearby Brooklyn courthouse just needs a place to play. Mark Manders vies with Jaume Plensa in Rockefeller Center and any number of CEOS for midtown's most cracked and swollen head. His Tilted Head in dark bronze, at the entrance to Central Park by the Plaza Hotel (since replaced by gaunt horses by Jean-Marie Appriou), could be a fallen totem, but with the crude marks of the artist's hand. At its back, a suitcase and chairs could stand for its place between civilizations. Now if only you could begin a journey somewhere far away.

A carpet of grass

Not all of summer sculpture cares about escaping into orbit or falling in ruins. Up in Marcus Garvey Park, José Carlos Casado cannot let even a bird take flight. Still, he has the perfect answer to I Don't Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (Ah, Me): it is made of aluminum party balloons, and the lightest in helium or in spirit rise to the top of the cage. Less conspicuous, on a pedestal partway up a hill, a female head of motorcycle tires, by Kim Dacres and Daniel A. Matthews, speaks for the dark side. Let her out of her cage, and she will burn black rubber.

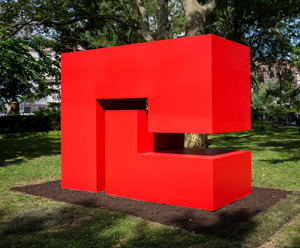

Not every artist breaks new ground at age one-oh-four, but then not every artist breaks out with a Whitney retrospective at over one hundred. Carmen Herrera has a gift for small tweaks to the picture plane that disguise their boldness—and big forms that disguise their subtlety. Her Estructuras Monumentales take them into City Hall Park and the third dimension. And monumental they are, each in a single color. Slim right-angled planes, their vertex pointing up, may recall the pro forma Minimalism of Ronald Bladen back in the day. Yet they keep one looking, to tease out their structure and its relation to contained or surrounding space.

Could Joseph La Piana make the most site-specific use of the Park Avenue ever? His polyurethane banners never do manage to follow the direction of the avenue or its median strip. In fact, they seem on the point of collapse. The title, Tension Sculptures, only accentuates the tension, and their canary yellow makes no bones about how little they fit in. They look left over from a construction project that failed to clear out before summer sculpture could begin. That, though, is precisely why they are site specific to New York.

If sidewalk construction has mostly missed Park Avenue, thanks to zoning laws, the boulevard might need some shaking up. The scaffolding elsewhere and its absence here alike are signs of extreme wealth. La Piana's reference to industrial parts underscores his ties with Minimalism, too. His title in fact refers to the tension within a banner, held up by steel poles at each end (since replaced by figurative cutouts by Alex Katz). Some angle around a third or fourth pole as well. If the poles in any one sculpture tilt successively toward the earth, that fragile regularity points to both late Modernism and real estate.

If sidewalk construction has mostly missed Park Avenue, thanks to zoning laws, the boulevard might need some shaking up. The scaffolding elsewhere and its absence here alike are signs of extreme wealth. La Piana's reference to industrial parts underscores his ties with Minimalism, too. His title in fact refers to the tension within a banner, held up by steel poles at each end (since replaced by figurative cutouts by Alex Katz). Some angle around a third or fourth pole as well. If the poles in any one sculpture tilt successively toward the earth, that fragile regularity points to both late Modernism and real estate.

Much as New Yorkers welcome summer sculpture, nothing is as welcome as a carpet of grass. Leonardo Drew lets the grass of Madison Square Park show right through—much as Erwin Redl converted the lawn into a field of winter light (and much like Leonardo Drew himself with gallery walls). Not to be outdone, City in the Grass brings carpeting of its own. It suggests the luxury of Persian carpets, and the tiered towers that interrupt it may seem exotic as well. I thought at once of Southeast Asian temples. Drew, though, is African American, and he embraces the city's rough edges as much as its grass.

The carpeting, he insists, is industrial, set on aluminum supports. It also boasts of its wear and tear, with those big gaps for grass. The towers pick up on the urban landscape, too—the top floors of the Empire State Building just blocks away. They also rest on a carpeting of scrap wood, which Drew based on a 3D map of the city. The model city of the 1964 World's Fair at the Queens Museum might have slipped closer to midtown. The wood also recalls his work in black, but one can still take time to watch the grass grow.

Alicja Kwade ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 27, 2019, and at 303 through May 18, "Chronos Cosmos" in Socrates Sculpture Park through September 3, Mark Manders at Doris C. Freedman Plaza through September 1, José Carlos Casado with Kim Dacres and Daniel A. Matthews in Marcus Garvey Park through September 30, Carmen Herrera in City Hall Park through November 8, Joseph La Piana on Park Avenue through July 31, and Leonardo Drew in Madison Square Park through December 15 and at Galerie Lelong through August 2. Simone Leigh ran on the High Line through next September 30, 2020, "En Plein Air" on the High Line through March 31, and Harold Ancart in Cadman Plaza through March 1. I continue to follow summer sculpture as in past years going back to summer 2003 and continuing through summer 2020 and its extension into fall, summer 2021, summer 2022, summer 2023, and summer 2024.