Taking Cartoons Seriously

John Haberin New York City

Philip Guston

Philip Guston painted with a passion for politics, the agonies of the avant-garde, a cartoonist's instincts, and the great American novel pent up somewhere inside. It adds up to one of the most stimulating, fiendishly self-indulgent, and influential careers in postwar art.

His influence started before he left L.A. As Philip Goldstein, at the start of the Great Depression, he turned the school paper into a protest movement. It got his friend Jackson Pollock expelled.

Guston's turn in the late 1960s to narrative painting seemed like the last nail in late Modernism's coffin. But was it heartfelt or flippant? Did it mark the birth of a new sensibility or a cranky, aging New Yorker's return to his old habits? A retrospective at the Met helps take the measure of a rebel with several causes, not the least of them himself.

A serious influence

Guston, who supplied the cartoons each week, got off easy. Not that Jackson Pollock bore a grudge. When he took his business—and modern art—elsewhere, he repaid his classmate by inviting him east.

In New York Guston fit in only slowly, but he made his name almost overnight. With a single work, executed in one sitting, he helped create the shift from American realism to abstract painting. Critics compared the loose weave of his surfaces to Impressionism. Without reference to women or landscape, without even such icons as rectangles or Barnett Newman's zips, they also stood for the purity of a new art. Their tight brushwork, intimate gestures, and muted colors remain visible in artists a decade younger, such as Joan Mitchell.

Just as suddenly, he put it all aside, with repercussions for artists between abstract and figurative today. Well into his fifties, frustrated by Richard Nixon and the war, he sought painting that could address a brutal world on its own terms. People still talk about his 1970 show at Marlborough gallery. Who else from the fabled New York School outlasted Abstract Expressionism, Alfred Leslie excepted? Like Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky, or Pollock, they self-destructed. Like Lee Krasner, they refined their glorious art to the end, at times risking tastefulness—or, in the case of Willem de Kooning, senility.

Guston made his decision when the divide between formalism and figuration really meant something, and it anticipated a postmodern return to painting and pop culture by nearly ten years. One can see his big, clumsy figures in Neo-Expressionism of the 1980s—or the turn to figuration in Milton Resnick as well. One can see his household detritus, hairy arms, and carefully staged confessions in shock art of the 1990s. One could easily mistake those naked bodies and pale, acid pinks for Susan Rothenberg's latest work on the cover of Modern Painters this very month. She would probably call it a compliment if you did.

His influence, however, can almost bury his intentions. Maybe history always works that way. His "Abstract Impressionism" can seem too formless and misty for its own good. The later piles of old shoes can look deliberately meaningless, like cartoons without a punch line. Either way, one could ignore him as a lightweight, reveling in an increasingly cartoon world. To critics, the air of profundity and rebellion collides with a cheery confidence and cheesy adolescent sex, as in Robert Crumb or, for that matter, the Britpack now.

Surprise! His retrospective shows a perpetual struggle for a more personal, meaningful art. Guston, it turns out, never gives up on the ideals of prewar American art. I may not like him personally, but I had better take him seriously. Make that dreadfully seriously. Consider, then, much the same history, but from a more somber perspective.

Abstract Depressionism

Like most artists of the 1930s, Philip Guston first knew two scales of art, the personal and the political. On the public side, he watched David Alfaro Siquieros, the Mexican artist and socialist, paint a mural for Pomona College. He worked on WPA commissions himself. An earnest, early sketch shows a hooded Klansman, like those who beat up gay men in a later painting by George Tooker. When he paints the horrors of war, a bare-chested man tumbles forward, in the viewer's face—a tribute as much to organized labor as to the showy anatomy and perspective of the Old Masters.

Guston saw himself following Piero della Francesca and the early Renaissance. To me, his thick faces and angular backgrounds look more like the late realism of Giorgio de Chirico or Francis Picabia. Ironically, like Guston himself, Picabia's turn from Dada to figuration came into fashion in the 1980s.

The personal meant realistic, easel painting, and smaller early works have the dark colors and heavy outlines of painters like Ben Shahn. The personal meant another kind of darkness, too. Born to Canada's long winters, Guston experienced a father's suicide and a brother's accidental death. At home, he worked in a small room by a bare bulb. For a Jewish artist, these motifs help further personalize his first renderings of the Holocaust. Throughout his life, he saw the world's chaos as his own.

In 1952, the year of that fabled abstraction, he was ready to make it completely his own. He picked up the brush and did not put it down until he was done. Over a thin white ground, he centers small, thick stokes of off-white. A few wider strokes, in stronger colors, rest upon the center of these. In the ensuing years the central colors and the canvas itself grow larger, darker, and heavier.

The abstract improvisations reflect Pollock and others. So does the formalism implied by a strongly centered composition. The intermediate layer of white, connecting color to canvas, also serves as bridge from painting as composition to painting as an object in the world. Clement Greenberg had to admire this. Yet Guston never really embraces formalism. He paints carefully, and both the canvas and the brush stick to the scale of easel painting.

It remains his scale and never that of the Sublime, just as the sober grays and dark patches recall his early realism. Forget associations with Impressionism, too. He has no use for the glowing color, all-over compositions, or mural size of Pollock or of Water Lilies by Claude Monet. Like Guston's eyes, this work never grows misty. It has a marked continuity with his first strivings for personal meaning, from his father's depression to the economy's. Call it Abstract De-pressionism.

Victim as victimizer

In a sense, Guston comes home to Abstract Expressionism only when he abandons abstraction. His peers had blown up the language of Surrealism and the unconscious to the space of Cubism and the scale of political art. By 1969, the canvases and patches of color had grown to the point that he had to break free of easel painting. He had to let himself into the picture. An artist this obsessive and conservative could pull it off only through representation.

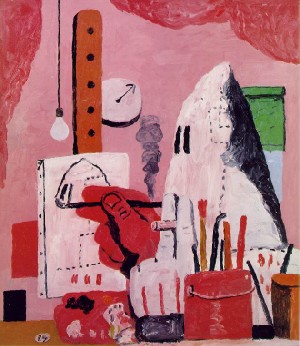

In his first rendering of the Holocaust, he identifies political violence not with the camps as for Si Lewen, but with a family's self-destruction. When he at last allows the personal to become public, he again identifies with victim and victimizer. He paints himself in his studio, but hooded like his old Klansman or a new one for Wardell Milan. Upturned legs stick up alongside his brushes, as if painting has to mean throwing human life out with the trash. A huge fist aims accusingly at the artist. The finger of God turns up again in a work just before Guston's death in 1980, like a last reminder of painting's sins.

Forget the idea of a surrender to popular culture. Instead of Roy Lichtenstein's Mickey, one gets the artist, who unlike Mickey may not live to so ripe an old age. Instead of James Rosenquist's alluring advertising, one gets swollen limbs. Instead of brand-name sneakers, one gets old shoes. The piles of them, critics have noted, echo the remains found in concentration camps. Guston's painted hero also wears them to bed, next to his wife. Again he simultaneously identifies with the victim and brutalizes those around him.

This self-consciousness may grow ponderous, but never humorless. Guston portrays himself, with an old man's ailments, as his own arch-enemy, Nixon. One might recall that Philip Roth, a friend of the artist, wrote a scathing comic biography of the former president—not to mention novels about himself as a creator and a Jew. The grandiosity and self-involvement come closer still to Saul Bellow. This art may look like a cartoon, but it aims for the great American novel. Guston's formalist critics had something right when they called his painting illustration, even if they failed to value it.

Guston lacks Roth's quick wit and dizzying self-reflections, but both come with a heavy dose of irony. One sees it in the subject matter and the ambivalence toward the artist. One sees it in Guston as creator and as fiction. One sees it in the pink backgrounds, at once the rawness of inflamed flesh and the lusciousness of paint. One sees it in the cartoon style. Just in case one forgot the continuity with his Depression Era days, he derives that style not from Crumb, whose comics he did not even know, but from Krazy Kat.

Ironically, the artist's sense of a heavy burden led to Rothenberg's gorgeous dreams of freedom. His love of artistic tradition, political activism, and obsession with the past bore fruit in Neo-Pop's world without a history. His illustrated, cartoon novel inspired a postmodern art wrapped up in texts. The great American novel found fulfillment in the global art world of the future.

Philip Guston ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 4, 2004. Related reviews look at the passage from Guston's abstraction, Guston's Klansmen, and Guston's self-doubt.