News of War

John Haberin New York City

Nabil Kanso and Si Lewen

Trenton Doyle Hancock and Philip Guston

Sometimes it seems that I have spent a lifetime listening to news of war and little but war. Just halfway through his twenties, Nabil Kanso must have felt the same. He spent the rest of his life bringing the news to others in paint.

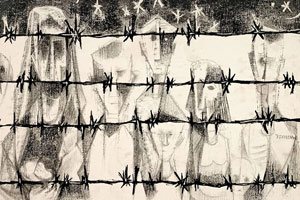

Si Lewen was a survivor, and the price of survival was to relive the Holocaust again and again. It was a price he was more than willing to pay. He relived it sixty-three times in one work alone, the drawings of The Parade—and again in the canvases that he called his Ghosts. Who would dare touch the Holocaust as a theme for art, and who could hope to portray the horror?  Do not dismiss its parade or its ghosts. After Kanso's seemingly endless and all but identical wars, they feel frighteningly specific and that much more real.

Do not dismiss its parade or its ghosts. After Kanso's seemingly endless and all but identical wars, they feel frighteningly specific and that much more real.

Of course, the War to End All War did not end war, and the Holocaust did not put an end to anti-Semitism. Racism in the United States has its own ugly history as well. Can a contemporary black artist and a Jew from another era face it together? The Jewish Museum opened its latest show the day after Donald J. Trump's reelection with an archival image of a lynching. Both Trump and the lynching drew larger numbers than I ever imagined. Draw your own conclusions.

A video cuts between the grainy photograph and still another spectacle—a carnival in Paris, Texas, where the black man in the photo suffered a grisly death. It lingers over colored lights and rides, with the cutest of animals as their seats. It lingers even longer over the moment before death. Nor is it the only image of a lynching in "Draw Them In, Paint Them Out," where Trenton Doyle Hancock "confronts" (as the museum has it) Philip Guston. Guston began drawing the mob nearly a hundred years ago, when its threat was all too real. Hancock to his delight is still catching up.

News from home

For Nabil Kanso, news of war was always news from home. He fled war in Beirut for the United States, knowing full well that it put him at risk of another. It was 1966, and Vietnam was already tearing apart his adopted country, but to him it must have felt like more of the same. He painted armies, civilians, and a ravaged landscape, because who can look at any of these without seeing pain? He did not live to know war's return to the Middle East and Ukraine, Yet the news he brings still seems altogether new.

It all blends together, but not to numb the senses. And he did paint Vietnam and the Lebanese Civil War, but a title speaks only of Accumulated Agonies. He worked large, as if to claim for himself the entirety of art history as well. He had seen Disasters of War from Francisco de Goya and Goya's graphic imagination, and he adopted Goya's explicit violence and accumulating darkness. Warriors and their weapons take up the foreground, with near horizontals at center for rifles and the barriers they penetrate. Their diagonals give the paintings a kind of architecture while adding to the chaos.

As the poem goes, ignorant armies clash by night. The scale itself calls for heroics and history painting. The paintings would not be out of place in the American wing of the Met, but heroes, too, cry out in cruelty and terror. The scale recalls another kind of heroism as well. Kanso came to New York when Abstract Expressionism was a living memory. Artists had to paint big and messy, with visible brushwork covering every inch.

He has, as far as I know, pretty much dropped off the map, although he himself worked on the business side of art, as a dealer. "All-over painting" was itself out of fashion. So were representation and sentiment, and I do not mean to canonize him now. Something was in the air, though, with the Neo-Expressionism of Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer, who looked back to the Holocaust and World War II. Kanso has something of their earnestness and, conversely, irony. He also knew the demand for color.

Kanso uses color for its own sake and for the horrors of war. It runs to blood red and fiery orange. Deep blue can suggest shadows, discolored flesh, or battle dress, perhaps from the Napoleonic wars. Color can also light up the anonymity of inarticulated faces. They can gather in arcs with red lips or in a crowd. One painting, though, sticks to a smaller canvas for a single face, The Confronting Mother.

Not that you would know its gender. Chalk white sets off large black eyes that speak of forced witness. Black tears drip from wide eyes, and flames run along its chin. Something or someone else intrudes at left, whether or not she can recognize it as hers. Maybe Kanso leaves so little explicit because he did not want to be known as the guy from Beirut. Or maybe he just knew at his death in 2019 that there would always be another war.

Survivors

Art Spiegelman first met Si Lewen as a survivor, at age ninety-four, as comfortable as he could possibly be with his memories. Spiegelman called him "a dynamo: a charming and elfin man, frail but bubbling with enthusiasm, wry humor, and unorthodox opinions." The younger man had come upon The Parade long before and must have felt it as a calling. It has the wit and brutality of his own account of the Holocaust in black and white, Maus, still years away. Its harsh lines and repeated elements anticipate the sheer existence of a graphic novel,  in an unnerving mix crayon, ink, pencil, and paint. If a cartoon version of the Holocaust sounds like a sacrilege, neither man was joking.

in an unnerving mix crayon, ink, pencil, and paint. If a cartoon version of the Holocaust sounds like a sacrilege, neither man was joking.

A parade can itself mean a procession of events from which there is no escape, like a parade of disasters, and Lewen's gallery compares Ghosts to shrouds. The very fact of repetition can characterize a nightmare, much as Arthur Jafa replays the horrific final shootings in Taxi Driver in video. And the Holocaust was a nightmare if there ever was one, from which Jews like Lewen are still trying to awake. Yet he was a survivor, again and again, and he took it as his chance to take history back from those who killed. If it can be hard to separate willingness from compulsion, he knew what he wanted.

Lewen had to keep reinventing himself to survive. He escaped Poland as a child and then Germany before it was too late. He joined the U.S Army rather than flee to safety, in a unit that valued his fluency in German language and culture. He participated in the liberation of Buchenwald without flinching, and he saw no need to put the events behind him once and for all. He took up a career that ties observation to action, as an artist. In one last reinvention, the Jew spent his last years in a Quaker home for the aged, where Spiegelman rediscovered him, four years before his death in 2016.

There nobody was marching anymore, but Lewen had lived for the parade. Much of his talent lies in riffing on that theme. He shows a pathetic excuse for a parade, with a German on horseback, and goose-steppers, again parallel to the picture plane. He shifts into depth for a very different procession, of men bearing the weight of coffins, but the parallels are inescapable. Perhaps some of the same victims face out from behind barbed wire, their hunger and terror not yet assuaged by the Americans they witness. This is the pageant that the Nazis demanded but could not control.

Repetition characterizes Ghosts as well, but the dead and living all but vanish. They become a patterning of hash marks within diamonds, with a pattern of their own. They link the series to the jagged line of German Expressionism on the one hand and to the Minimalism of his time in painting on the other. They amount to abstract art (and portions of The Parade approach abstraction as well), but as realism's ghosts. Still larger work, spanning five panels, screams at the horrors of war like Goya. Like the drawings as well, this could be a graphic novel rather than fine art, but not for want of care or provocation.

Two doors down in the gallery's street-level space, Kaloki Nyamai, too, is and his not playing around. He fits with other artists who are working not with African American life or the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, but a return to Africa. Nyamai paints Kenyans at work and play, but it is hard to tell the difference—or to separate figures in action from assorted body parts. Both float in a sea of scribbles and scumbles on acid blue and yellow ground, as Twe Vaa, or "we are here." He could be asserting his own sense of home or the existence of a people. Either way, you are there, unless you are lost as well.

Confronting the Klan

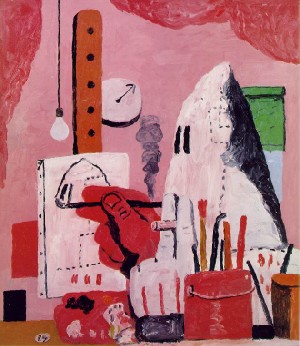

Born in 1913, Philip Guston has become a gallery and museum staple for his images of the Klan, including himself in his studio with blood-red hands and a white sheet over his own head. At first he earned anger and disdain for his turn from the comforts of postwar abstraction, later, as his fame grew and "mere" cartoons became fashionable, for his subject. Only recently Boston's Museum of Fine Arts came close to canceling a retrospective, opening at last without a black curator. An African American, Trenton Doyle Hancock is still based in Texas and still grappling with the same sense of guilt and the same fears. He was not even born when Guston returned to that theme in 1969, but the Klan haunted him from an early age as well. One can still ask just who is confronting whom.

Guston's early drawings have a nasty realism, Hancock's a loaded ambiguity. In a photograph, he lies on his back in a corner completely covered by a sheet. He could be a dead body left for disposal or a Klansman catching up on sleep. Guston's later figures are closer to caricature, with a nose borrowed from Richard Nixon. Often he sets just two figures side by side, as the artist and his model or the racist and his victim. He may never have left the studio for all one knows, but it is scary enough inside.

Hancock has much the same pairings, but with a recurring hero, named first Loid and then Torpedoboy. The character is at once captive and superhero. He is also both a participant and an observer. He may turn white from shock, far whiter than the murderer, or pitch black as if seen through the white man's eyes.  He also has more colorful pop-culture scenery, like the fair grounds. Paintings get much of their colors from plastic cups and lids. In ink on paper, dialogue or commentary runs wild without offering a pat resolution.

He also has more colorful pop-culture scenery, like the fair grounds. Paintings get much of their colors from plastic cups and lids. In ink on paper, dialogue or commentary runs wild without offering a pat resolution.

The controversy is not just about putting a good face on black experience in today's culture-affirming art. It is about who has the right to speak for whom. Born in Canada to Ukrainian Jews, Phillip Goldstein grew up in LA from age 6. His parents had found safety and must have hoped for, well, normalcy, but he never could. You will recognize the turn against him from the 2017 Whitney Biennial, where a white artist, Dana Schutz, dared to paint the open casket of Emmett Till. They were taking responsibility for what they fear most.

Black artists, too, face their share of shoulds and should nots. Kara Walker has had no end of complaints for appropriating stereotyped black silhouettes. Should an artist paint only what she sees in the mirror, and should a male novelist incorporate only men? Should art stop speaking out against bigotry? I sure hope not, and I appreciate the sheer cacophony of voices at the Jewish Museum from just two artists. As Hancock has it in a recurring title, Step and Screw!

I have written way too much elsewhere about Guston, but then this is Hancock's show by far. Yet the more time he spends on Guston, pouring through the estate in preparation for this show, the closer he feels. Did Guston paint a ladder to the sky, as his approach to memories? Hancock's hero thrusts one leg through a ladder of his own. His are big canvases and maybe a bit silly, and I cannot tell the show's four themes and sections apart, but daring and controversy go a long way. As a Jew in my own way myself, I can feel the mob growing closer and the spectacle all too real.

Nabil Kanso ran at Martos through October 5, 2024, Si Lewen at James Cohan through April 27, and Kaloki Nyamai through May 4. Trenton Doyle Hancock and Philip Guston ran at the Jewish Museum through March 30, 2025. Related reviews look at at Guston at the Met and in Chelsea.