Local Heroes

John Haberin New York City

Henry Taylor and Spike Lee

And Ever an Edge

Martin Luther King, Jr., took his case to the people. He could not have inspired so many had he not, but who knew that he was such a regular guy? Who knew that he was just another part of the black community and its local heroes?

At least he is in memory for Henry Taylor at the Whitney. The civil-rights leader stands beneath the trees in a place that you, too, might like to call home, with a clunker of a car that could not quite bother to fit into the picture. The kids beside him see nothing out of the ordinary in his presence—or in the football in his hand, winding up for a pass. If the March on Washington had not been so huge, the Mall might have made a terrific playing field.  For Taylor, the real black heroes are always with him, waiting for him and you both to receive their greatest gift. But then a self-portrait can be England's Henry V from the Tate.

For Taylor, the real black heroes are always with him, waiting for him and you both to receive their greatest gift. But then a self-portrait can be England's Henry V from the Tate.

I would be insulting Spike Lee if I said that his collection is more about him than about art. What else should guide a collection but passion? The alternative is what someone thinks will sell. Of course, that passion should extend to the world around him, but no problem there. If one thing holds together four hundred items at the Brooklyn Museum, it is a passion for New York. It may not be much as, strictly speaking, an art collection, but this is his New York and very possibly yours as well.

Not that Lee's sense of what matters is any less real. It just happens to filter through African American eyes in Brooklyn. He grew up there, though born in Atlanta—first in Crown Heights, just blocks from the Brooklyn Museum, and then in Cobble Hill, when it was still Italian. In every sense, he is returning home. He bases his production company there, too, Forty Acres and a Mule in Fort Greene. His first film, She's Gotta Have It, is about a graphic artist in Brooklyn, and it could almost look ahead to "And Ever an Edge," the Studio Museum artists in residence at MoMA PS1.

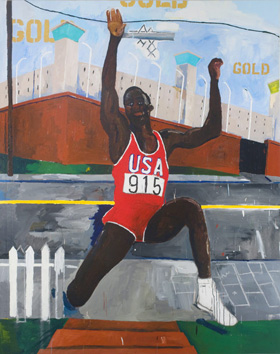

Taking a pass

Born in 1958, Henry Taylor painted King only recently, but every inch of Taylor's life is as vivid as yesterday. Did he number King among his heroes? Surely, but also the Black Panthers and others who turned to confront a violent nation. And do not forget artists, friends, and family. Besides, like David Hammons, they were often one and the same. Taylor's brother was active in the Panthers in Oakland, before retiring to his family's home state, Texas, to breed dogs.

They demand a great deal, much as King wears a suit just to play football, and one of the kids shows up in a tie. The car is a spotless white. Huey Newton of the Panthers sits, armed and enthroned in a peacock chair, as in a well-known photograph—and the artist often works from photos in search of heroes, much as in 2010 at MoMA PS1. He also works from paintings, much like Bob Thompson and Barkley L. Hendricks at home in a museum, and he cites as models the social satire of Max Beckmann, Philip Guston and Guston's Klansmen, and Francisco de Goya in his Third of May. He poses Eldridge Cleaver after Whistler's Mother and adapts a portrait by Gerhard Richter to Cassi Namoda, an artist from Mozambique. He numbers whites among his artist portraits as well.

King with a football notwithstanding, Taylor cannot take his heroes off their pedestal. Still, he is not just rubbing it in. He is not, like Mickalene Thomas and Kehinde Wiley, making strangers and street people into icons. If anything, work from the 1990s mocks icons and their pedestals, with found sculpture and painting on the likes of malt liquor and cereal boxes. He can face the darkness, in black skin or in death at the hands of the police, and the discomfort. A little girl dresses up for her mother, but The Dress, Ain't Me.

At times he seems almost determined to fit in. The curators, LA MOCA's Bennett Simpson with Anastasia Kahn, call the show his "B Side," the more experimental side of the record, but do not believe it. He grew up in California and studied at Cal Arts, where he sketched skillfully and well. He comes closest these days to the casual realism that has become the mainstream thanks to Alice Neel. Still, he comes by his caring naturally. He worked ten years at a state mental hospital, on the night shift.

He has his own way with Neel's style, too. He makes maximal use of white with seemingly accidental traces. He also keeps his sense of humor. He calls one champion athlete See Alice Jump. Darker, flatter colors pull a painting from 2017 close to abstraction, because (in full caps) The Times Thay Aint a Changing, Fast Enough! Frowning or grinning kids can look sullen or sinister.

He has a knack for taking heroes as friends and friends as heroes a concern for Marcus Leslie Singleton as well. Still, he cannot avoid the temptations of either one. A man at the grill for the Fourth of July is barely an individual, much less a shock. The exhibition stopped me in my tracks just once, with a whole room for the Black Panthers as store mannequins, like a revolution's empty suits. Still, you can always be grateful for cornbread fresh from the oven. Taylor's mother made it herself.

A passion for Brooklyn

As for Spike Lee, this is a filmmaker's collection through and through. It opens with posters for his movies (the first in Haitian Creole, also spoken in Brooklyn) and returns often to movies. One room has posters for the classics that were just changing minds when he was growing up, from Rashomon and global cinema to The French Connection on the streets of New York. It has music, including musical numbers from his films. Lee's father was a jazz bassist, while his mother taught. It has no end of sports figures and their uniforms, especially his beloved New York Knicks.

What it does not have is much art worth remembering. It has Deborah Roberts and Michael Ray Charles, African American painters with a style rooted in folk art of the South, and Kehinde Wiley with a sitter in Jackie Robinson uniform. Mostly, though painting appears, often as not anonymous, as designs for prints—whether posters or the cover of Time featuring Toni Morrison. Not that it downplays the visual arts in favor of Lee's development. While the curators, Kimberli Gant and Indira A. Abiskaroon, call it "Creative Sources," he is not giving anything away. Everything on display is complete except for America itself.

That is cause for celebration and a reminder of struggle, racial struggle, just as in his movies. No one appears as often as Malcolm X. In show's first video, Malcolm speaks at a rally, he explains, not as Democrat or Republican, Christian or Jew, because blackness preceded them all. Am I an arrogant white male if I say that this is my history as well? I have not taken a show so personally since "Analog City" in 2022, and Lee, I think, would approve. This is the city that shaped me, too, only starting with Lee's work itself.

These are the books I read, the vinyl I heard, the movies I saw. I cannot tell you how much time I spent alone in my room listening to Knick games in 1969 and 1970, the year of their coach and starting five in a portrait here. When Brooklyn burns in Do the Right Thing and good intentions die, my city was burning, too. Anyone who grew up in those years might feel the same way. Who would not envy a first edition from Zora Neale Hurston? Who could not envy guitars from David Byrne and Prince—or brass from Branford and Wynton Marsalis?

If the story can also be yours, credit Lee's passion and open mind. Gordon Parks and Richard Avedon photograph cultural icons, black and white (while Carrie Mae Weems photographs Lee himself). A thematic arrangement avoids a single story as well, requiring one to double back on one's tracks to exit. That has the advantage of avoiding an unhappy ending, with a clip cutting from a Klan march to Donald J. Trump's talk of "fine people"—and a bat from Aaron Judge the year the Mets and Yankees imploded. If the show still sucks up to celebrity, with too few surprises and too little art, I can understand. This is a museum with its own weak spot for the neighborhood.

The chill winds of home

A chill wind blows through the art of Charisse Pearlina Weston, but a powerful one. All three of this year's artists in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem feel the chill in their own lives, and all three look for shelter from the storm. Jeffrey Meris goes so far as to include body casts of himself and his mother, because attachments matter, and so does the search for identity.  Devin N. Morris paints an ordinary black kid on an ordinary city street, mounted above a chest of drawers. He even mounts a door right on the wall. Welcome home.

Devin N. Morris paints an ordinary black kid on an ordinary city street, mounted above a chest of drawers. He even mounts a door right on the wall. Welcome home.

For all that, they know displacement, even as their art has found a home For the fifth year, MoMA PS1 wraps up the residency with an exhibition while the Studio Museum is closed for expansion and renovation. Meris was born that much further away, in Haiti, but he is not, so far, looking back. He adds warmth and color to his paintings with magazine clips that look suitably commercial and American. Never mind that they include photos of red blood cells, already ominous enough. They must be so for him, who has a compromised immune system.

Lest you doubt it, he needs crutches to walk, and a sphere of crutches pointing out hangs from the ceiling at the center of the room, like a Death Star. He also paints with cuts into roofing materials, which themselves provide shelter while exposed to the elements. Those two body casts, both busts, fall well short of motherly love. They look badly damaged in their unpalatable white resin. Come to think of it, Morris hangs his door too high on a wall to offer access, and it leads nowhere. Another landscape seems about to be swamped by a tidal wave, and enormous eyes look out a window to spy on you.

It is all the give and take of survival and hope. Morris bathes his scenes in sunlight, and his assemblage moves easily from the city into nature. He paints young people beside a tree and on the grass, resting or reading, like his version of Luncheon on the Grass without the nudity and provocation. He also adapts the materials of home to nature. A chair leg becomes a branch, and scraps of paper become the trees of a young forest, where junk like key chains scatters color on the ground. More paper twigs serve as a shawl or the cape of a superhero.

Weston sticks to abstraction where, so long after Minimalism, you can expect a chill. Paintings stick to black and white or to white and a pale, icy green. The colors move across the image like sudden blasts, and she incorporates texturing so that the blasts seem to have shattered. Sculpture runs to heavier but still vulnerable materials. Glass breaks off awkwardly, etched with impenetrable text, and rolled lead might have curled up a moment before. The glass and steel give weight to and threaten one another.

Could they also take the shape of windows? One can make out curtains, peeling back but without a view inside. Weston cites a public program that sought to relieve the decay of the South Bronx and Harlem—but not by doing more to keep housing functional or to provide amenities. How about a few more windows with nicer curtains and potted plants? I cannot take "And Ever an Edge" as this year's exhibition title and its poetic diction too seriously, but all three artists do have an edge. They will just have to call it the edge of home.

Henry Taylor ran at the Whitney through January 28, 2024, Spike Lee at the Brooklyn Museum through February 4, and "And Ever an Edge" at MoMA PS1 through April 8. A related article picks up the Studio Museum artists in residence next year.