Sit Tight

John Haberin New York City

Paul Cézanne: Drawings

"It took him one hundred working sessions for a still life, one hundred fifty sittings for a portrait." And who can count how much more it took in drawing? With "Cézanne Drawing," MoMA shows him at work on paper every single day.

It is not just the Paul Cézanne of his paintings. A man with a pipe appears apart from his partner in a card game, intent on something unseen. Figures from the early bacchanals multiply and run wild. When Cézanne traces over their outlines and their musculature to emphasize and to coarsen them, they seem wilder still. Some signature motifs, such as card players or a portrait of his dealer, do not appear at all. Yet that just shows his drawings as fascinating for their own sake—and for hints to all that they leave out.

Only an essay?

All those sittings add up fast, but sitters could take comfort in how easy it was after all. They could work with Cézanne on choosing a pose, and they found him a willing collaborator. In portrait after portrait, his wife barely looks up from her chair. His gardener and handyman got time off from work. Cézanne came in the wake of some explosive realism, but he was not out to document class relations or everyday life in southern France. He cared too much for the individual and for his art.

They could take comfort, too, in contributing to some of the greatest paintings ever and essential steps toward modern art. They could, that is, had anyone realized it at the time. I began with a quote from Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the opening sentence of "Cézanne's Doubt." Maybe you think of Modernism as a matter of dated and oppressive certainties—of dogmatic formalism and dead white males. The French philosopher tried to recapture its probing and questioning. And nothing to him typified that more than Cézanne's self-questioning and long, hard work.

Sitters could take comfort as well in what the numbers leave out. Along with those sessions and sittings, Cézanne's art took a lifetime of drawing. For Merleau-Ponty, "What we call his work was only an essay, an approach to painting," but was it? The Modern shows him at work on paper day in, day out—to learn, he explained, "to see well." With some two hundred fifty works, this is as close to a retrospective as you are likely ever to see. And I left with my doubts about Cézanne's doubt.

Merleau-Ponty wrote at the end of World War II and the dawn of the atomic age, with everything in doubt. He wrote, too, as philosophy was embracing existentialism and a broader culture was embracing existential crises. (His "phenomenology" has gone down in the books as a precursor.) In art, Europe's competing schools were dying or moving to America, where Abstract Expressionism was just then putting the artist on the line. When he writes of Cézanne's work as "only an essay," he makes him the first "action painter" far ahead of his time. In calling the show "Cézanne Drawing" rather than "Drawings," surely MoMA agrees.

One cannot get past the questioning, but one can feel from the start the exhilaration and the confidence, so that even a show of drawings can be among the very best of 2021. The exhibition opens with two self-portraits, of just his face. He is smiling in one, unemotional in the other, and both rely on the same parallel pencil marks to fill out his beard, the shading, and his expression. Artists before had made a point of their youth, like Albrecht Dürer, or their grimacing, like Jean-Jacques Lequeu and David Hockney—to show life at its limits and to show what they can do. Cézanne feels no need to exaggerate. He sees what he sees, and he has the tools to pull it off.

Would the confidence last? Not necessarily, but the exhilaration lasts. Like Merleau-Ponty, history has favored his late work, where doubt left Cézanne with everywhere to start and nowhere to stop. It meant returning to views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, overlooking Aix-en-Provence, as if to a dear and stubbornly distant friend. It meant pressing his brush against canvas over and over, but without producing a thick, clotted surface. Meyer Schapiro wrote in 1959 of the late work's "epic largeness" and "ecstatic release," and that applies all the more to the greater lightness of works on paper.

From murder to mountains

Cézanne hit on his toolkit early, and the show pauses midway through to explain. He works almost exclusively in pencil and watercolor, in mostly red, yellow, and blue. With a medium to soft pencil, he can sketch impulsively and then go back over the outlines to add to their stability or chaos. He can daub freely in watercolor or leave whole areas blank, so that the paper, too, is a medium for his art.  In one of his most colorful drawings, a skull on a yellow table is gleaming white. In late work, white and color mix so freely that one hardly knows where they begin and end.

In one of his most colorful drawings, a skull on a yellow table is gleaming white. In late work, white and color mix so freely that one hardly knows where they begin and end.

As with his self-portrait, he returns to the same sheet or the same subject again and again. He might do so right away, to see what he had missed, or for decades. He worked on single sheets and in sketchbooks, and MoMA has plenty of both. The curators, Jodi Hauptman and Samantha Friedman with Kiko Aebi, arrange things by subject, to balance his insistent return with his chronology. It takes him from his first look at himself and family and his dense early narratives, with their pencil redoubling and, occasionally, gouache. It ends with the largest and freest watercolors, with hardly a pencil mark in sight.

Those early narratives are dark indeed. They run to rape, murder, or sheer indulgence. They include the temptation of Saint Anthony, whose visions exemplify madness and human folly for Hieronymus Bosch and Salvador Dalí. Even when turns from his crowded inner world to studies of a plaster cast, the plaster cupid looks half crazed. For an artist so associated with modern rigor, Cézanne began as a moralist, with the moral directed more than half at him. If there is a key to his development, it is learning to show himself and his subjects, from his gardener in profile to a plate of pears, a greater respect.

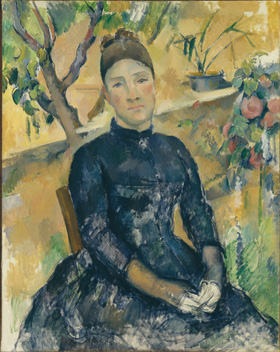

After more museum studies, he looks to the open air and cuts lose. Central rooms have his bathers and his family, to which he returned the longest. He depicts his son as a harlequin and his wife in their conservatory garden. They can seem at once intimate and remote. Bathers look off or toward a ground with barely a trace of water. His wife betrays little in the way of intelligence or affection.

He also returns often to still life—and not as decorative arrangements or allegories of death. Fruit look fresh after all those sessions, without the spoilage in classic still life, with its nature morte, or "dead nature." A coast on a chair seems about to rise up all by itself. And then at last comes the Paul Cézanne one knows best, in landscape, with trees and rocks at Fontainebleau and his own personal limestone mountain. Rocks solidify and leaves dissolve in the flurry of color and white. Dead branches take on a life of their own.

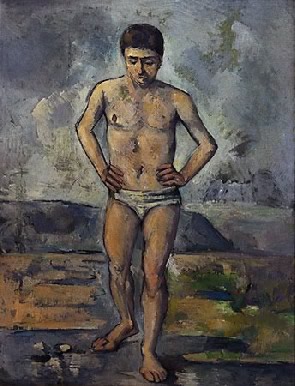

The Modern also includes more than a handful of paintings, three of the best from its collection or the Met's. In Le Grand Baigneur, or great bather, arms akimbo and hands to the waist, solid form enters wide-open air. With a boy in a red vest against a near abstract background, Cézanne finds his most intense color, without abandoning a mood of private contemplation. With Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory, he learns that a blank face and blank angled wall need not cut off the eye or the light. They come close to taking over the show. So was Merleau-Ponty right after all, with the drawings as only an approach to painting?

Doubts about doubt

They could instead show his drawing and painting as parallel investigations. As Schapiro put it in 1968, "There is a genius of his watercolors other than the genius of his oils." Drawing might also offer a key to what textbook dismissals of his early work leave out. Just why did he abandon narrative—and did he really? And that leaves open how much he overcame his neuroses and his doubts. For an answer, one might turn to another early self-portrait study, where he shares the sheet with an apple.

Paul Cézanne wanted to show both as alive, but he also sets the apple against his balding forehead, as twin sculptural forms for the ages. He needed always to work from observation, but for work, he said, "as solid as the art of museums." In Schapiro's words, he cannot distinguish "an underlying, esthetically more potent, geometric form from the particulars of nature." But could he reconcile the two? He does even in his single most academic study, a model in his studio. Against all odds and proper teaching, one remembers most the man's face.

It may not sound like it, but he does so, too, with the potboilers. He places them in a tradition of narrative painting, quoting Peter Paul Rubens and what he called the "apotheosis" of Eugène Delacroix. He is drawn to Francisco de Goya, the master of torments and grimaces, and Goya's graphic imagination. He would hardly mind if a banquet scene made you think of The Wedding Feast at Cana by Paolo Veronese in the Renaissance. After all, in his Paris years he went to the Louvre every day. For Cézanne, the art of museums was not simply the art of the past.

Less obviously, the most sordid narratives are not all that far from the demands of modern life. They might be right out of a novel by Emile Zola, long a friend and champion. (They split after Zola used him as inspiration for L'Oeuvre, or "the work," about a painter who never does find an audience for his genius.) They are even closer to Edouard Manet, who set his nude Olympia, after Titian, in a brothel. Cézanne also copies a Goya portrait, but not as a rebel in the house of kings. He sees instead a self-assured dandy—not unlike the Parisians who disdained the awkward young painter from Aix-en-Provence.

Ultimately, he became truest to observation and the art of the museums only by abandoning contemporary realism and the quotes alike. He could sketch a rockface with an eye to both its geological foundation and the fall of light. He could set the white of the paper against the material reality of nature and paint. He could break with past and present, to discover what they mean for the future. By the standards of academic painting, Impressionism, or the similarly fragmented but museum worthy Pointillism of Georges Seurat, his brand of Post-Impressionism really does look incomplete. Those standards, though, are incomplete as well.

It may no longer make sense to speak of doubt, if that implies failure rather than the determination to go on. "When a picture isn't realized," he protested, "you pitch it in the fire and start another one!" Still, Merleau-Ponty gets at something real. For the artist, he says, observation is experience—something not just seen but lived. For all the apparent distance, Cézanne's many sketches of his wife's face can be filled with love. That love just happens to extend to mountains.

Paul Cézanne and "Cézanne Drawing" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 25, 2021. I quote Schapiro from his book on Cézanne in the Harry N. Abrams Library of Great Painters and from his essay on "The Apples of Cézanne: The Meaning of Still Life," in his collected papers on modern art. Related reviews look at Cézanne's card players, his landscapes compared to those of Camille Pissarro, his portrait of Vollard, and his portraits of his wife.