Taking It Easy

John Haberin New York City

Michael Hurson, Laura Owens, and Byron Kim

Michael Hurson, Laura Owens, and Byron Kim have it easy. Dancing eyeglasses and idle hands lazing across five a dozen clocks. Private pools and well-furnished bedrooms. Intimate friends and fairy tales. Sundays off to take in the sky.

They also have serious claims for painting. Like artists before them, from Henri Matisse to Pop Art, they ask to strip representation down if not to pure painting, than to pure pleasure. Hurson did so amid the New Image Painting of the 1970s, Owens and Kim amid the eclecticism of art now. She even refashions a museum on its behalf. Can they have it all?

One for the deep end

David Hockney was not the only artist entering the 1970s by poolside. True, he was swimming in attention, while Michael Hurson had yet to make a splash. Hockney had also come to California from a seamy but swinging scene in London, while Hurson was from the Midwest, native to the unfulfilled promises and turmoil of America in the 1960s. His colors are earthier or just plain absent at that, with nary a watery blue in sight—not even for a series of Palm Springs swimming pools. Paintings look much like sketches, with firm indications of place and sunlight still to come. Yet he, too, was having fun.

He could always count on himself to get up and dance—or, if not, on his eyeglasses. They move across schematic but fiery landscapes, several pairs at a time, and down a pillar-shaped canvas. They stand in quite well, thank you, for academic nudes as the artist, then entering his thirties, no doubt could not. One might take their side pieces for legs and their frames for musculature. They turn their lenses on nothing in particular, least of all the viewer, but they earn a second look. They could well be about the space between looking and acting.

They and the swimming pools placed Hurson at the forefront of New Image painting, like Susan Rothenberg or his friends Jennifer Bartlett and Robert Moskowitz. He had already had solo shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and MoMA when he exhibited with them at the Whitney in 1978. Those pools and dances are (if you know Bartlett) his Rhapsody. He has, though, sunk more into the past, and one can see why. A show spanning thirty years clusters near its start, as curated by Dan Nadel. It also had me thinking of the problematic brilliance and shallowness of Hockney.

Like Hockney, he never verges on Minimalism or darkness like Rothenberg or Moskowitz, and he never explodes across a room like Bartlett or teases apart the sheer possibilities of painting. Yet both have a teasing emptiness. A single figure lies on a blanket to the side, as if unable to enjoy a dip or a deck chair. The pool takes on a peculiar mass, like a truncated pyramid. Like Hockney, too, Hurson keeps looking away to distant mountains. A drink and cactus in the foreground of one chasm parallels the Brit's still-life with landscape in homage to Japanese art.

Like Hockney as well, he found a supporter in Henry Geldzahler, the curator, but he grew closer to Modernism as Hockney never could. A third series contains portrait sketches with a flatness and density akin to Cubism. The eyeglasses as bulky nudes may deserve comparisons to Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso after all, although the swimming pool lacks for Matisse bathers. They could offer a bridge from the early twentieth century to Pop Art. The show ends six years before Hurson's death from heart failure in 2007, at age sixty-five. One may never know whether he was every quite ready to dive into the deep end.

As the show opened, the gallery's space across the street was exhibiting a younger artist who is. Cecily Brown again packs quotations from art history into a contemporary Abstract Expressionism. Can you spot the borrowings from The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault? Me neither, but an enormous mural has everything else you might wish, including faces, bodies, and shards of color. It and other paintings look brighter than humanly possible with barely a hint of red or blue. Like Hurson, she keeps the threat of water at bay.

The end of her rope

Laura Owens takes the museum's proverbial white cube literally, as a room within her midcareer retrospective at the Whitney, and paintings wrap around its top. In one painting on each exterior wall, a single hand sweeps along like a clock that has lost track of everything but the precious seconds. The rest might be counting off the hours more figuratively, even if having fifteen rather than twelve in each row disrupts space and time once again. Another partition cuts off all but the top of a few more rows on a back wall. Sneak into the narrow corridor behind it for the rest, should you dare arouse a museum guard's vigilance. Two more paintings face one another as mirror reflections, give or take the artist's imperfections.

Still another installation treats its paintings as bedroom furnishings, with a painted couple in bed hung just around the corner. Given three beds, five dressers, and two bedroom mirrors to multiply them, this would be quite a slumber party. Jorge Pardo, her boyfriend at the time, contributed the stiff and seemingly mass-produced furniture. And then there are the paintings within rooms within rooms within paintings, like the one with an easel and a perspective onto other galleries at back. Either this imaginary museum welcomes copyists, or Owens has enlarged her studio. She does so implicitly every step of the way.

Owens pays tribute to a great museum. Still cherish the movable walls and flexible galleries of the old Whitney on Madison Avenue, now the Met Breuer? The 2015 architecture by Renzo Piano extends them to larger spaces downtown. Now the Whitney brings them to much of two floors. And yet Owens began her paintings more than twenty years ago, and she and the walls are still on the move. Do not believe her one minute when she says that she is at the end of her rope.

Despite all appearances, her retrospective is anything but site specific. The curators, Scott Rothkopf with Jessica Man, base its rooms on her past shows—and that painting of a museum, first exhibited in London, contains her distorted memory of the Art Institute of Chicago. She plays freely, too, with boundaries in taking Minimalism's grids into wood slats that may extend beyond a painting's edge. She plays just as much with memory, with a style out of children's books and subjects out of the lives of her children. Her son contributed a homespun fairy tale to four freestanding panels. As a likely museum first, she brought her little girl to the press preview.

The delights of a child at play extend to mythic lovers and warriors, nature scenes, and slapdash abstraction. And the overt sophistication extends to the illusion of thick brushstrokes on classified ads—or knots of paints that stand for birds and bees. Owens has lived in LA since attending CalArts, where John Baldessari made conceptual art the order of the day. She reasserts painting, in accord with its revival nowadays (like her appearance at MoMA in "The Forever Now"), but conceptualism is still on her tail. It follows her even to the naive and the painterly, like the circle of light from a table lamp. Who knows whose eyes or stars peek through as blurred circles of light in a dark forest?

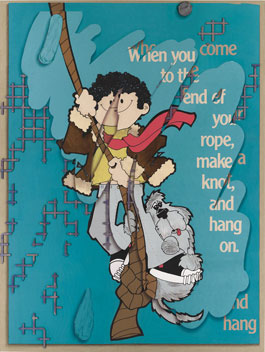

Owens does not often do darkness or depth, although the space aliens in her son's fractured fairy tale may have leveled cities. She is more at home with her grandfather's sailboat or the birds and the bees. As the text of one painting puts it, "When you come to the end of your rope, make a knot, and hang on." A cartoon boy and baboon take her advice, happily ignoring the irony. So much LA whimsy can wear quickly, but one can still enjoy the exuberance—not to mention a painting's way of referring to itself and others. Go ahead and feel impassive, but the museum walls have given way.

Send in the clouds

I can grow so bored by On Kawara that I never stop to ask: is he bored, too? Does he ever get so sick and tired of painting the date in plain block letters on a plain colored field, to the point that it becomes an obligation? Or is it rather a relief to have a still point in a turning world—or just a way of life? Is the act of painting as ordinary for him as a walk around the block and a glimpse of the sky? Does it make every day at once part of an ongoing chain of thoughts and a fresh start?

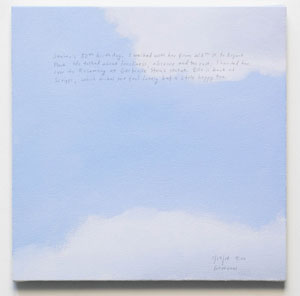

Byron Kim must feel all of the above by now. Every Sunday for more than seventeen years, he has devoted a square just fourteen inches on a side to a patch of sky with nary an airplane, apartment tower, or telephone pole in sight. The "Sunday Paintings" range from light blue to a cloudy white. Then he adds the date, time, location, and whatever else crosses his mind, in pen or pencil. Anyone can do the math to see that the series is approaching nine hundred paintings, and almost no one will follow every word in a selection of roughly a hundred. Still, dipping in and out will make them part of your chain of thought, too.

Byron Kim must feel all of the above by now. Every Sunday for more than seventeen years, he has devoted a square just fourteen inches on a side to a patch of sky with nary an airplane, apartment tower, or telephone pole in sight. The "Sunday Paintings" range from light blue to a cloudy white. Then he adds the date, time, location, and whatever else crosses his mind, in pen or pencil. Anyone can do the math to see that the series is approaching nine hundred paintings, and almost no one will follow every word in a selection of roughly a hundred. Still, dipping in and out will make them part of your chain of thought, too.

They have obvious affinities with abstraction or color studies, like squares for Josef Albers, and Kim did appear a decade ago in "Color Chart" at the Museum of Modern Art. Their mundane subject recalls his choice then of skin tones. They also fall in a tradition of precise notes of the weather by landscape painters and of cloud studies by John Constable, but without the painstaking complexity. After seeing Constable sketches more than twenty years ago, I wrote that he handles clouds like portraits of dear, departed friends. Kim handles them more as elements in an unfolding self-portrait. He adds a new work each week over the course of the show.

For a while the inscription covered a separate strip at the bottom of the canvas, but now it can fall anywhere, as the sky and his thoughts have become one. Locations like Gowanus are a reminder that Kim also appeared in "Open House," a show of Brooklyn painters. The rest of the words spin off into the triumphs and stresses of family, friends, and politics, from pleasure in the first black president to the shock of a Sanders supporter after a year of Donald J. Trump—and from the comforts of familiars to fears of letting them down. They can read like a Facebook entry, a haiku, or a secret. New Yorkers who frequent art galleries are likely to recognize themselves as well. Artists frustrated by the system can, for a moment, almost feel at home.

Sunday paintings demand regular habits and stern promises. When Kim misses a week, he notes it the next time with regret. Yet they also suggest time off from work. Instead of muddying or challenging abstraction and representation, he can embrace both. Instead of charting colors, he can let them fall where they may. He can accept failure along the way, much as in relationships. Whatever else, there is always another Sunday.

The series may have come to him as a new beginning. It starts on January 7, 2001—the first weekend of a new year and a new millennium. For those less into grand pronouncements, it was also just another day. A need for reassurance may account as well for the cheery palette, even when Hurricane Sandy darkened galleries. Kawara must have felt the same need, as in a series of nearly a thousand telegrams, each with the very same text: I AM STILL ALIVE.

Michael Hurson ran at Paula Cooper, through December 22, 2017, Cecily Brown through December 2. Laura Owens ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through February 4, 2018, Byron Kim at James Cohan through February 17.