Seoul on Ice

John Haberin New York City

Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea

Lineages: Korean Art at the Met

Korea was changing fast back then, but not that fast. In his slideshow of life on the streets and in the news in Seoul, The Meaning of 1/24 Second, Kim Kulim does not come close to twenty-four frames per second. This is a photomontage, not a movie, and he knows it.

For all that, the world was spinning out of control, with only artists to give it substance and, just maybe, meaning. Does Kim exaggerate? Such is youth, and this is "Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea" at the Guggenheim. This was 1969, a time with a spectacular youth culture, the year of Woodstock and Abbey Road. Here in the West, too, late Modernism was coming under assault. If art in Korea from the 1960s and 1970s seems less familiar and less consequential, it more than kept up.

Korean art has a place of honor in any museum's Asian wing, but it may still struggle to free itself from the intoxicating presence of China and Japan. What can match their legacy in ceramics and ink—or in portraiture and landscape? What can match their art's restless hands and sensation of contemplation and rest? Would it help to include recent art, as a point of departure into the past? The Met does just that in its Korean gallery, as "Lineages." The result, though, says more about the present than its ancestry. It also confirms a disturbing trend in museums today.

So much for organization

The very first work at the Guggenheim reels off the changes. Yet White Paper on Urban Planning, by Ha Chong-Hyun is neither white nor obviously urban. It is a colorful abstraction, on paper of course. It has no particular pattern holding together its soft curves, hard edges, and horizontal bulges, but then it casts doubt on the very possibility of planning. So does Kim, with The Death of the Sun and Tombstone. Someone must have planned for the future, but not for their thick, black, charred remains of vinyl, steel, and plastic.

Photographs next to both describe a newly westernized Korea, with only a touch of exaggeration, much like Kim's slides. Fashionable young people crowd the streets, and black highways spin out from their intersection five ways. Whoever could plan for this? A Japanese invasion and World War II had left the peninsula divided, and the Korean War only confirmed the division. And those wars were only the start of an American presence. Global capitalism was bringing high rises, highways, industrial cities, and fashion.

Art responded, with its own scattershot attempt at organization. Movement after movement arose, with little to set off one from another. Kim helped found the Fourth Group, and I lost count after the Korean Avant-Garde Association, Space in Time, and whatever else. Their members made a point of not attending the official art show each year, although they had no qualms about exhibiting in biennials in São Paulo and Paris, where they made a hit. The madness leaves their retrospective with no clear themes or sequence. The curators, the Guggenheim's Kyung An and Kang Soojung Korea of Korea's National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, have three tower galleries for eighty works by half as many artists.

Abstraction appears often, but as collage, like three rows of four creased circles apiece by Ha Chong-Hyun. Ha Chong-Hyun constructs his dense monochromes from acrylic, cigarette butts, and matchsticks. He also lays barbed wire over coarse jute rather like burlap. As art, it has its inclusions and exclusions, like the middle class, the Demilitarized Zone, or a barbed-wire fence. Kim makes his abstraction from rows of light bulbs that will never light up. As painting, these are forgettable, but the point is their tactile value and the remains of the day.

Overtly political art is rare, for all the nation's felt tensions. It is implicit in a gas mask and backpack set against harsh yellow, from Lee Taehyun. It may or may not be implicit in an upside-down map of Asia by Sung Neung Kyung or the brash self-assertion of his photographs, his face a battleground. Magazine clippings lie on the far side of a window frame by Yeo Un, but with more celebrities than headlines. Sung leaves shredded newspapers to accumulate in boxes, but not, photos attest, without reading them first. Just in case any of these artists needed one, Shin Hakchul supplies a pair of scissors.

Nature is rarer still, in art so focused so on the capital city and its post-industrial debris. Does nature even exist these days? Lee Kun-Yong mixes red concrete with gravel and soil as the base for a tree, as Corporal Term, while Lee Seung Jio abstracts away from PVC piping. Park Hyunki has reflections on rippling water, but on TV, like a monolith. He uses rough stones as support for a TV, too, with a nod to Nam June Paik. He holds the TV in his arms as well, in photographs and performance, and it looks heavy.

Abstraction and sensation

Nature and abstraction alike have become theater. The transience of performance art reflects the transience of life, like Kim's one frame per second. It reflects, too, art's attempts to master time and change, with little more than the artist's body. Lee Hyangmi may speak of Color Itself, but one can feel the force of gravity in its vertical drips. It is a long way from the control or surrender of drips for Jackson Pollock. Kang Kukjin may speak of Visual Sense, but for thin, rising neon tubes akin to those of Robert Irwin or Dan Flavin.

Is there method to their madness? Lee Kun-Yong speaks of The Method of Painting and The Method of Drawing, but their only method is adding marks until running out of space. He speaks of a Logic of Hands, but for a cryptic sign language, and a Logic of Space, but for stepping in and out of a circle. Lee Kang-so commits to painting, too, but on camera, behind the glass pane on which he works. Others make a ritual from eating, pouring drinks, or, like Kim, just sweeping up. Shim Moon finds the nuances of monochrome in sanding cloth, while Kim Youngjin takes abstract sculpture from the plaster imprint of his flesh.

They evoke the rigor of Minimalism and the bodily sensation of Post-Minimalism, like that of Senga Nengudi and Eva Hesse in the United States. Lee Kun-Yong has his Corporal Term, Choi Boonghyun his abstraction as Human Being. They bring the same sensibility to Pop Art as well. Jung Kangja displays enormous lips as Kiss Me. Song Burnsoo prints a face in five colors that could pass for silkscreens by Andy Warhol, but they look downright scary. But then Warhol, too, had an abiding awareness of death.

Can there still be a uniquely experimental art? Was there ever? The question arose as early as Postmodernism, with such critics as Rosalind E. Krauss. It arises day after day in the galleries, where seemingly anything goes. Asian art today seems especially prone to convention, with science-fiction images and anime. The very notion of experimental art, silheom misul in Korean, dates not to the period it describes, before 1980, but to Gim Mi-gyeong decades later.

Asian-American art included such figures as Paik, Lee Ufan, and Yoko Ono. Its influence reached to the West as well, with what older artists called "the third mind." One will not encounter any of that here. Today's idea of change would also demand a greater diversity and respect for tradition. Lee Seung-taek alone had a fondness for antiquities. He translated what he saw into large ceramic vessels tapering at the top like flames.

Do not be surprised if you do not recognize a single name. Do not be surprised, too, if you fail to find a single woman. Still, their interest in film anticipates younger Asian artists turning to video art, including Korean video. Credit them, too, with a fluid space between stasis and change, abstraction and performance. As I left, I passed Gego on the museum ramp, from Venezuela. In light of Korea's experiment, half a planet away, her wire constructions seemed newly relevant.

Points of departure

More, and more, museums of art history consider themselves homes to modern and contemporary art as well—and it can cost them, as the Met learned in leasing the Met Breuer. One can see the appeal. Collectors must like a confirmation of their tastes, and that can translate into donations and gifts. The public may like a change from that boring old stuff others call art, and that, a museum hopes, can translate into attendance. Still, it takes money, too, and it can positively detract from older art. The Met's modest Korean gallery has room for just thirty-two works, and now half are contemporary.

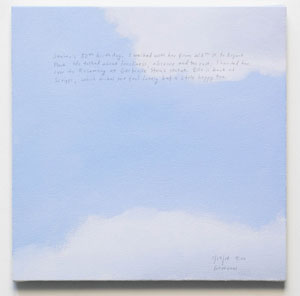

Who knew that Korean and Korean American art so much as had a deep past? Such luminaries as Lee Ufan and Byron Kim have a more obvious debt to Minimalism. (Hmm, maybe artists do not have to be "original" after all in order to stand out, now or long ago. They need only be aware of their world.) The Guggenheim situates Korea of the 1970s in a drive toward youth and experiment. At the Met, Nam June Paik proclaims that Life Has No Rewind Button, and a pioneer of video art should know.

Who knew that Korean and Korean American art so much as had a deep past? Such luminaries as Lee Ufan and Byron Kim have a more obvious debt to Minimalism. (Hmm, maybe artists do not have to be "original" after all in order to stand out, now or long ago. They need only be aware of their world.) The Guggenheim situates Korea of the 1970s in a drive toward youth and experiment. At the Met, Nam June Paik proclaims that Life Has No Rewind Button, and a pioneer of video art should know.

Yet they do have a past, more than you ever knew. Ufan's abstraction appears right after Bamboo in the Wind by Yi Jeong from more than seven hundred years ago and Blood Bamboo by Yang Gi-hun in 1906. Their vertically descending stains become his descending blues. It is From Line at that, surely a call-out to those who have worked in ink. And then come ink and gouache on paper strips by Kwon Young-woo in 1984 and a wild web of ink lines by Suh Se Ok in 1988.

Kim, in turn, has two monochrome panels in deep green, as abstract as one can get. Yet its glazes echo the materials that convert white porcelain into the paler green of celadon. Older Korean art perfected both. Their polish contrasts with the endless invention of Japanese ceramics, on view out in a corridor overlooking the Met's great hall. I have my doubts about Kim, but other contemporaries have been eyeing the serenity and symmetry of older "moon jars" for sure. Seung-taek Lee makes his own in 1979, with the illusion of a bit of rope on top to tie it up, while Kim Whanki paints one back in 1954, in yellow on a red pedestal against soft green.

Of course, a jar may be the subject of still-life or a thing in itself, and the Met dedicates the gallery's four walls to line, persons, places, and things. (Well, that should cover it.) It sounds innocuous enough, although line can become landscape, and landscape can take one to freely imagined places. Park Soo-keun in 1962 lingers over women beneath a tree, in textured oil, at once people and places. The most prominent person, a woman scientist from Lee Yootae in 1944, owes more to mid-century realism and a growing appreciation for professional women than to tradition. And sure, jars become things, at the center of the room, with two by Lee Bul in 2000 as the foot and pelvis of a cyborg.

One can still value a golden age that lasted nearly a millennium, until Europe sailed right in. Indeed, one had better. Where Chinese art once admired those who gave up power to stand outside of place and time, Kim Hong-joo in 1993 creates a layered, divided landscape, which the Met sees as commentary on a divided Korean peninsula. I prefer to think that Hong-joo got it right, but the Met still gets it wrong. Does my resistance to the contemporary make more sense in Asian art, which so often provided a greater tranquility? I just hate to see the past crowded out and forgotten.

"Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through January 7, 2024, "Lineages" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 20. A related article looks at Korean video art.