Swing Time

John Haberin New York City

Paula Wilson, Virginia Overton, and Rachel Harrison

Are things getting a little crowded? Some artists have too many media and motifs to fit in a gallery.

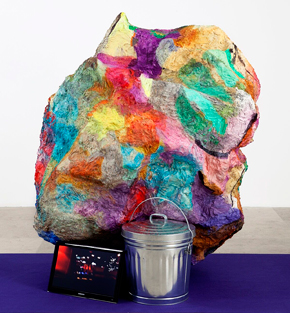

Paula Wilson, for one, comes right off the wall and so does woman's self-image. Just up the street, Virginia Overton has all but a car crash, only shinier. Overton had already brought sculpture gardens to the Whitney Museum's lofty terrace, with an emphasis on both the artifice and the garden. Soon after, with her playground set out in Astoria, she had the world of art on a swing, and now she is coming for Tribeca. Meanwhile Rachel Harrison has what looks richer still. It might be as transient as the wind, but it is colorful enough for me.

Fun, fun, fun

Paula Wilson serves up not just a show, but a compendium of her art. Now that nontraditional materials have become almost a requirement, she brings no shortage of those as well. Weaving has become an assertion of women's work as fine art, and Wilson leads straight to what must surely pass for just that. It might be a self-portrait, only larger than life, or an empty dress. At a time, too, when glass and ceramics have attained dignity as art and design, she gives mixed media a history in stained glass. Steel tracery outlines an image, while gallery light passes through like sunlight.

In a show called "The Wind Keeps Time," first impressions may soon be gone with the wind. Wilson has a reputation as a mixed-media artist, and the show includes video as well, but she is still a painter with a trust in imagery. I first encountered her in summer group shows in 2013, with an entire catalog, as I wrote then, of painting, architecture, and remembered pleasures. She executed it, though, in tapestry, or so I think, but it simulated bricks, grillwork, decorative reliefs, and graffiti. Here what looks like something else entirely is most likely a print or acrylic. Only a true painter would see its potential for imagery and light.

That portrait stands face front at the center of the back wall, at the gallery's second, shared space up the block from its first. The rest fills the room in front of it, largely apart from the walls. If that suggests a chapel dedicated to the artist herself or to women, it includes simulated stained glass. It frames a girl's image as well, the silhouette of a dancer in sunlight. It might almost be a magazine clipping—and the entire show a kind of collage. Wilson treats pretentious claims as free play.

Virginia Overton, too, takes materials off the wall as something tangible and a place to play. Her 2016 terrace sculpture for the new Whitney Museum, as you will see in a moment, gave it a reflecting pool or perhaps a real one. Her 2018 summer sculpture in Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens turned brown steel into a swing. She also parked the very symbol of American freedom out front. Did that mean a car? She may not have taken one to the principal space for Wilson's gallery, but then Tribeca parking is a nightmare.

You may find yourself thinking of cars facing silvery metal inside the gallery. You may feel the momentum of a moving car from its physical presence as well. Her most impressive work fills the long central wall with foot-wide strips of it, rippling across the space. A smaller work fills three walls of a side room. Up close from the moment one enters, it demands attention to beaten metal and to every bolt. Thin, darker beams curve apart from an apex at the top, held together by a clip even as they threaten to fly away.

Overton has salvaged them all from the archetype of the great American highway, a sign, which she disassembled strip by strip, beam by beam, and bolt by bolt. The gallery's Web site shows none of this—only cars parked outside an establishment that I hope never to patronize. Puzzling or not, it rings true. The house number on the building behind them even matches that of a pricier Tribeca dealer right across the street. Park yourself inside to relish the shine before it fades. Art will have fun, fun, fun till her daddy takes the T-Bird away.

Renewable or preserved?

Among the pleasures of the new Whitney, the museum finally has a sculpture garden. Make that "Sculpture Gardens," in the plural, thanks to Virginia Overton. Her terrace sculpture looks singular enough, like her shiny car on a gallery wall, although all three components come in multiples. They partake of the same benevolent vision of nature—and of how cities like New York can renew themselves by responding to it. Step inside, though, where Overton has a gallery to herself and, as a more direct route outside, a narrow corridor. Suddenly the argument between nature and culture resumes where it left off.

The Whitney never had a proper sculpture garden at what is for now the Met Breuer, not even that basement moat. Now its terraces make the best way to move from floor to floor, compared to less prepossessing stairwells. The building by Renzo Piano aces yet another test as well, in dividing the fifth floor galleries among Overton, Stuart Davis, and Danny Lyon. Its first shows exploited differences in size and natural light by keeping to separate floors. A lobby display of June Leaf holds a more subtle triumph over the old building, with a table for found objects amid her "primitivist" nude paintings—like Calder's Circus but with childhood dreams fallen to industrial debris, bodily decay, and dust. Nature versus culture gets yet another life.

That argument is a mainstay of art and civilization, going back almost as long as either has existed. Scholars in the Renaissance and Romanticism loved it. While it sounds quaint in art today, where nature and culture alike tend to come in quotes, it may well take on new urgency thanks to global warming. A journal called Nature and Culture in fact devotes itself not just to landscapes, political and otherwise, but also to environmental technologies and renewable energy. So does Overton. Standard-issue backyard pools become aquatic gardens, and tall windmills spin furiously in the Hudson River breeze. Tree trunks, one side sliced off cleanly, supply benches to contemplate it all.

Is this nature or intelligent design? The black windmills power absolutely nothing—although they do pump air into the pools, keeping the plants in motion. The sheer activity in the water suggests less renewal than disarray. The benches raise fears for old-growth forests despoiled not just by industry, but even by art. They also raise fears for the sculpture in light of ordinary museum traffic. The day before the public opening, the Whitney was still debating whether people could sit on them.

For the show's sequel, "Winter Garden," the mills turn more furiously in the winter wind. And the tubs, now inverted, serve as drums to amplify what normally passes for silence. Back inside for Overton's first segment, things get messier still. The corridor has attractive enough wallpaper, of clouds and southwestern canyons, but with nowhere to stand. The larger gallery has more tree trunks, sliced just as cleanly, but as a plinth with the rough sides facing inward and one another. In each case, nature is turned inside-out.

That leaves a bundle of pipes suspended from the above, like clouds but also like materials for the Whitney. It leaves another trunk, the kind not from a tree but for a journey, papered with more reminders of the great outdoors—and it leaves an actual smoked ham. If you mistook it for resin, you could be forgiven for wanting something less gross. Is it nature or culture, preserved or renewable, an unhealthy meal or a threat? And yet some of Overton's materials come from her family farm. Both indoors and outdoors can still offer gardens.

Cardboard idols

There are visionaries, and then there are visions. Art museums are filled with the former, but Rachel Harrison had to high-tail it to New Jersey to find her visions. Not that Harrison counts among the most storied visionaries at MoMA, and it took a camera and some scavenging to make the visions hers. The artist has a fascination with the dregs of mass culture and icons to bad taste, so naturally she skipped down to Staten Island and across the water to Perth Amboy. And there other pilgrims flocked for the icon to end all icons, the appearance of the Virgin Mary.

Erwin Panofsky did not have tabloid headlines in mind when he wrote Studies in Iconology in 1939, to look afresh at Renaissance painting and to ask: what does art show, and what does it mean? Harrison is asking the same thing, only about kitsch. Her twenty-one photographs show the same plain clapboard house from only slightly different points of view. Palms clinging to its windows look ever so real, because they are, but they seem to have appeared from somewhere beyond. The paler reflections in glass might hold other faces, other visions, or nothing at all.

They also hold the show's brightest colors, almost like stained glass, just in case one is still looking for the Virgin or for art. It takes some effort, however, to see them. Perth Amboy is an installation, its center a maze of brown cardboard.  Each step along the way could serve as a shipping container or a pedestal, but missing its baggage or its cardboard idols. Maybe, like the people in New Jersey, you will come with your own. The cardboard sheets stand on end only half-folded anyway, unable to enclose more than museum-goers. They slow one's pace, so that every so often one catches a photo on the wall and a vision.

Each step along the way could serve as a shipping container or a pedestal, but missing its baggage or its cardboard idols. Maybe, like the people in New Jersey, you will come with your own. The cardboard sheets stand on end only half-folded anyway, unable to enclose more than museum-goers. They slow one's pace, so that every so often one catches a photo on the wall and a vision.

Not that they stand much in the way of circulating freely. They do not connect up, and they are only cardboard. As mazes go, this is a throw-away, like multiple Donald Trumps recently at her Chelsea gallery. It does, though, hold a few additional surprises, and sure enough they mostly stand on pedestals. Harrison has been scavenging again in all the worst places, and she pulls her finds together as miniature works of art or installations. They also depict further visions.

This is not a movie. Still, further description feels like spoilers. Suffice it to say that a ceramic Chinese scholar peers at a rocky crag, while a seated doll contemplates a wall of solid green—the tarp of a construction site as seen in a photograph, maybe just across the Hudson. An Indian chief sets eyes on a glowing landscape, sunglasses set aside as if to bathe that much more in the illumination. Two dalmatians take endless pleasure in an iceberg made of more cardboard surfaced in white.

More colorful debris might represent another pedestal, made of drinking straws crumbling in all directions, if without half the luminosity of plastic drinking cups for Tara Donovan. And one last idol could well be yours. The bust of a reddish blond baring her shoulders occupies an actual cardboard box. You may come away with the pleasure of a casual stroll through the Modern, a celebration of disposable America, or a skepticism about art and visionaries, with the only laying on of hands by ordinary human beings a few miles away. Or you may just write off the whole thing as Harrison's growing obsession with bad taste. Either way, you get to consider competing visions.

Paula Wilson ran at Bortolami through August 30, 2024, Virginia Overton through August 9, 2024. Earlier, Overton ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 15, 2016, and June Leaf at the Whitney through July 17. Rachel Harrison ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 5, 2016, and at Greene Naftali through June 18. Overton returned through February 5, 2017.